Health

We Are Pushing Nature to the Edge—But Solutions Are Within Reach: Global Conversations on Sustainable Health

Published

12 months agoon

By

Mak Editor

By Davidson Ndyabahika and Johanna Blomgren

We’ve all done it—tossed leftovers, ignored wilted greens, or shrugged at a half-eaten meal. Food waste is a quiet guilt we all share, a reflex in a world of abundance and scarcity. But what if this small act connects to a larger global issue? On February 26, 2025, experts from Uganda, Sweden, and beyond gathered in a virtual seminar, asking, “How can we nourish ourselves without harming the planet?” Hosted by the Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Health (CESH), the discussion revealed a harsh truth—our food habits are draining the Earth.

The discussion on sustainable food systems marked the beginning of the annual four-part global conversation on sustainable health, organized through a collaboration between Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet and Uganda’s Makerere University under the auspices of CESH.

In Kampala, the paradox is stark. Every day, 750 tons of food waste fill the city’s landfills, enough to feed thousands. Rotten mangoes spill from crates in Nakasero Market, and half-eaten Rolex wraps pile behind street stalls. Uganda’s Food Rights Alliance shows 37.8% of this waste comes from plates and markets. Across East Africa, organic waste, like spoiled vegetables and discarded tubers, makes up 79% of urban trash—a grim reflection of broken systems. Beyond this is a city stuck with piles and piles of organic trash, which has previously been fatal with a slide in one of Kampala’s major landfills. Meanwhile, 26% of Uganda’s children remain stunted.

At the heart of this week’s global conversation was the WWF’s Living Planet Report 2024, a sobering revelation of a 73% decline in global wildlife populations since 1970. Freshwater ecosystems have hemorrhaged 85% of biodiversity, Latin America’s species richness has plummeted by 95%, and Africa—home to smallholder farmers who feed millions—has lost 76%. “Nature is disappearing at an alarming rate,” warned Harold Turinawe, WWF Uganda’s Forest Markets Transformation Manager, his voice weighted with urgency.

“We are pushing Earth’s systems to irreversible tipping points, and despite the increase in food production and land use and the destruction of habitats, the world is still hungry; we have over 735 million people going to bed hungry every other night. The contradiction is striking,” Turinawe added.

The report highlights the Amazon’s lush canopies that are felled for cattle ranches. The interplay of man’s unsustainable utilization of Mother Nature, leading to the food paradox, feast, famine, and ecological ruin, underscores the urgency of addressing global goals in a coordinated manner.

The report’s indictment of industrial food systems is clear: agriculture claims 40% of habitable land, 70% of freshwater, and drives 25% of greenhouse emissions. Yet, 735 million people still starve nightly. “Our obsession with monocultures and processed foods isn’t just destroying habitats—it’s failing humanity,” said Dr. Rawlance Ndejjo, the seminar’s moderator and a public health lecturer at Makerere University.

Florence Tushemerirwe, a Ugandan public health nutrition expert based at Makerere University’s School of Public Health, pointed out the irony: 26% of children are stunted, while obesity rises among adults in Uganda. “We grow nutrient-rich crops but export them, leaving people dependent on cheap, processed imports. In fact, many people do not appreciate their nutrient value,” she said. Uganda’s iodine-depleted soils now rely on fortified foods—a temporary fix for a growing crisis.

All through the seminar, the message was clear: we are wasting abundance while ecosystems crumble and people go hungry. “Our salt is iodized because our soils no longer provide it. Biodiversity loss isn’t abstract—it’s stealing nutrients from our plates. But if we don’t maintain our nature’s health, or our environmental health, or our natural resources health, it means that whatever food we grow, we actually do not carry the nutrients we need to maintain a diverse diet,” said Tushemerirwe.

The panel dissected global food trade’s role. WWF’s Turinawe lamented, “90% of deforestation is for agriculture. In Uganda, the once-vibrant wetland ecosystems of Lwera at the shores of Lake Victoria now face severe degradation due to large-scale rice growers; in the Amazon, its cattle ranches.”

Dr. Rachel Marie Mazac of Stockholm Resilience Centre stressed Europe’s complicity: “Sweden’s ‘virtual biodiversity loss’—importing deforestation via beef and soy—shows how our diets export destruction.”

“From a Swedish perspective, we are highly dependent on imports, particularly raw materials, which contribute significantly to biodiversity loss in other regions. It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact impact, especially with biodiversity, but there’s a concept of “virtual impact,” says Dr. Mazac.

Food consumed in Sweden, though produced elsewhere, contributes to biodiversity loss in those areas. The issue links to trade, food production, and distribution. It’s not just about production or waste but also equitable distribution.

Dr. Ndejjo added starkly, “You could be eating a burger from a cow grazed on razed Amazon forest. Guilt isn’t enough—we need systemic change.”

Amid the grim statistics, the panelists outlined a roadmap for redemption: nature-positive agriculture, subsidy policy reform, improved localized diets, global accountability, and honest discussions on the GMO dilemma.

Turinawe emphasized the need for agroecology in extension services—integrating trees, crops, and livestock to rebuild soil health and biodiversity. He stressed while critiquing Uganda’s Parish Development Extension Model for prioritizing enterprises for profit over sustainability. “We are saying get one million to a farmer. What are they producing? They are engaging in commodities that are predetermined. Nobody’s talking about Mother Nature. Who takes care of the soil? Who takes care of the water needs? Who takes care of the diversification we are talking about? But diversification in the diet begins with diversification on the farm. So my first issue is strengthening the agricultural extension services,” says Turinawe.

Adding that things like soil health management, land tenure system farmer-to-farmer network for peer learning, and fair farmer subsidies should be key to planning and agricultural extension.

“In Uganda, where I come from, and currently in Kampala, if you head north towards Zirobwe in Luweero District, you’ll find people we call Bibanja owners—essentially squatters who don’t own the land they occupy. These individuals cannot engage in sustainable agriculture as we’re discussing; their focus is survival. What we need are programs that give farmers secure land rights, which can motivate them to invest in soil health and environmental conservation—investments that take time. Improving soil is not a short-term effort; it requires long-term actions like planting trees, integrating practices, and using farmyard manure. None of this is realistic for someone who fears being displaced tomorrow. We need to approach this challenge collectively.”

Subsidies must reward sustainable practices, not industrial giants.

“Why not tax breaks for farmers using organic manure?” Turinawe challenged. “I would love to hear that a farmer that is engaged in sustainable cocoa production and coffee production gets a tax holiday rather than having a blanket of investors getting a holiday. Put subsidies and investment incentives in the right direction. We shall spur production, and of course, this will also bring in corporate partnerships, and we can make our supply chains safer, better, more green, and more sustainable,” Turinawe added.

Dr. Mazac noted that “nature-positive production can feed the world by optimizing crops, livestock, and wild fisheries, and supporting aquaculture that works with wetlands, not against them.” For Mazac, policy is key: She is also an advocate of subsidies and taxes that benefit farmers. Those that ensure incentives that improve soil health and maintain water quality as well as tackle climate change in order to make sustainability profitable.

“We must rethink trade to avoid widening the gap between food-producing areas and markets and instead support local farmers. Subsidies and taxes should empower these communities to nourish their populations before focusing on exports. While exports generate income, they also have significant impacts. A possible solution is changing production systems, but we must also shift dietary and consumption habits, making this a collective effort, not just an individual responsibility.”

Tushemerirwe is hungry for reviving indigenous crops and regulating predatory marketing. “Awareness is power. We must teach communities to value their traditional foods over processed substitutes.”

“There is good food grown in rural areas and available in markets, but people don’t recognize its value due to lack of guidance. We need food-based data guidelines to raise awareness. The Uganda Ministry of Health has a draft for this, along with draft policies to regulate unhealthy food marketing, especially to children. Junk food is advertised everywhere: hospitals, schools, and even street billboards, with fast food chains clustered together. We must regulate this and educate people on the nutritional benefits of eating what they grow over imported alternatives,” she stated.

Dr. Ndejjo believes these draft guidelines to regulate unhealthy food marketing should be finalized into policies and urges policymakers and implementers to prioritize the urgent need for these documents.

The conversation also weighed in on the genetic engineering in agriculture for increased crop yields, popular for GMOs, a dilemma that panelists called for their democratization rather than demonizing them. While Dr. Mazac cautioned against corporate-controlled seeds, Turinawe acknowledged their potential: “If democratized, drought-resistant crops could save farms in a warming world.”

Dr. Mazac noted that while in Europe and the European Union, they are not allowed to grow or sell foods that have been genetically modified, the essence of them should not be overlooked, since they are a technology that seeks to solve the future food crisis.

“GMOs aren’t inherently evil. Drought-resistant crops could save farms—but corporate patents trap farmers,” she said.

Turinawe added, “Our approach to GMO’s is a measure one bordering more on ethics and responsible use of GMOs; we see GMOs as a tool to promote resilience, especially since everything has changed—the food we once relied on can no longer grow in the same way. If GMOs help improve crop resilience, that’s a valuable tool. However, there are concerns that companies like Monsanto could use the GMO technology as a tool of exclusion, e.g., the fear of monopolizing future seed markets. This is where caution is needed.”

A Call for Radical Collaboration

The seminar’s resounding theme was unity: multi-sectoral collaboration is non-negotiable. From street food vendors to policymakers in the boardrooms, every actor must align. “Food systems aren’t siloed,” Dr. Mazac asserted. “They’re woven into climate, economy, and culture.”

“I think we need to sit and agree and engage quite regularly and find solutions for us to be able to produce food but sustainably,” concluded Tushemerirwe.

The Path Ahead

CESH’s global conversations on sustainable health are a microcosm of a global awakening, especially in tracking progress to meet our goals for 2030 and beyond: This seminar on food systems emphasizes the interconnectedness of food security and biodiversity. With the next UN Climate Summit (COP29) on the horizon, the panel’s message is clear—transformative change is possible, but only through courage, equity, and an unyielding reverence for nature.

To find more about this global conversation on sustainable health and more, visit CESH.health

Davidson Ndyabahika and Johanna Blomgren are the co-organisers of the global conversation on sustainable health

You may like

-

76th Graduation Highlights

-

Meet Najjuka Whitney, The Girl Who Missed Law and Found Her Voice

-

Makerere University School of Public Health Graduates First Cohort of Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Short Course

-

Climate variability found to shape malaria trends in Yumbe District

-

Mak hosts First African Symposium on Natural Capital Accounting and Climate-Sensitive Macroeconomic Modelling

-

Uganda Martyrs Namugongo Students Turn Organic Waste into Soap in an Innovative School Project on Sustainable Waste Management

Health

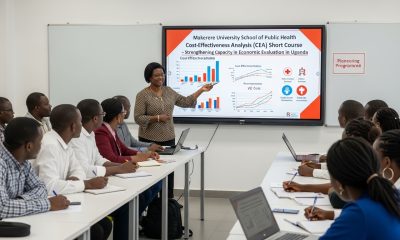

Makerere University School of Public Health Graduates First Cohort of Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Short Course

Published

4 days agoon

February 20, 2026By

Mak Editor

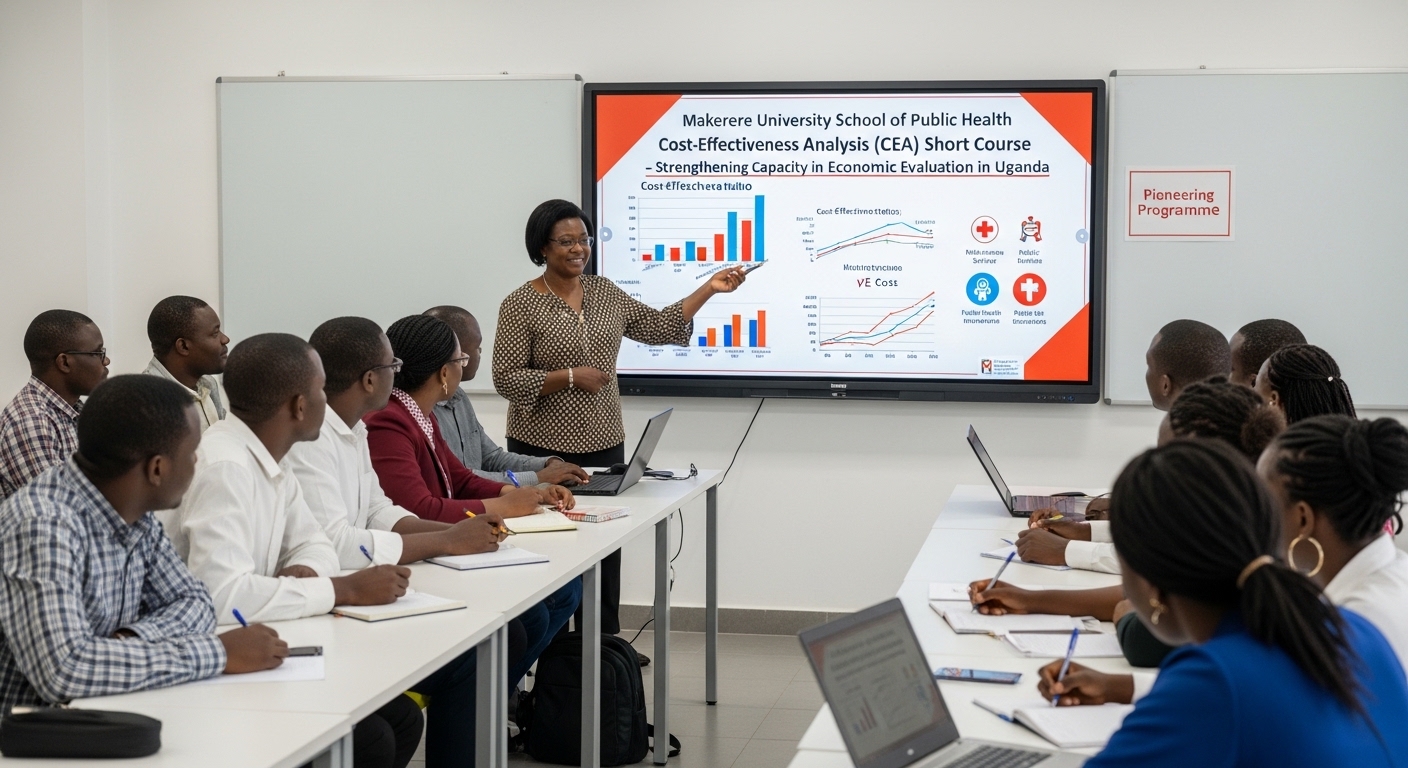

Kampala, Uganda – The Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH) has marked a significant milestone with the graduation of the first-ever cohort of its Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) Short Course. The pioneering programme is designed to strengthen capacity in economic evaluation in Uganda and beyond.

The virtual graduation ceremony honored eleven (11) participants who completed the course. The cohort included professionals from academia, research institutions, government agencies, and non-state actors, reflecting the increasing demand for skills in economic evaluation across sectors.

The short course was developed and implemented by the Department of Health Policy, Planning, and Management (HPPM) in response to the increasing need for evidence-informed decision-making in a context of limited resources.

In her remarks during the ceremony, Assoc. Prof. Suzanne Kiwanuka, Head of the Department of Health Policy, Planning and Management (HPPM) at MakSPH, congratulated the inaugural cohort for completing what she described as a “critical and timely” course.

“With decreasing resources and rising demand for services driven by population growth and the emergence of high-cost technologies, decision-makers must make difficult choices,” she noted. “Cost-effectiveness analysis is no longer optional. It is central to conversations in the corridors of power.”

The CEA short course was designed to equip policymakers, researchers, and practitioners with both theoretical knowledge and practical skills in economic evaluation. Participants were introduced to key principles of health economics, costing methodologies, decision-analytic modelling, Markov modelling, sensitivity analysis, and interpretation of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

According to Prof. Elizabeth Ekirapa, the course lead at MakSPH, this inaugural offering had been “a long time coming,” following years of discussions within the department about building local expertise in economic evaluation.

Delivered over 10 days through interactive online sessions, the course combined lectures, case studies, and hands-on modelling exercises using contextually relevant datasets. Participants were required to develop and present applied cost-effectiveness projects as part of their assessment, allowing them to translate theory into practice.

During the feedback session at the graduation ceremony, faculty emphasized the importance of clarity in defining study perspectives, selecting appropriate outcomes, and aligning research questions with modelling approaches.

Dr. Chrispus Mayora, one of the facilitators, highlighted the need to carefully select outcomes that directly reflect the intervention being evaluated. “When thinking about outcomes, ask yourself: Is this aligned with what I want to study? Interesting outcomes are not always the most appropriate ones,” he advised.

Participants were also encouraged to select modelling techniques such as decision trees or Markov models based on the research question and the nature of the disease or intervention under study.

Prof. Ekirapa described the graduates as “trailblazers,” noting that their feedback would shape future iterations of the course. “When you are the first cohort, you are like pioneers,” she remarked. “We are committed to improving this course to ensure it becomes a world-class programme.”

For many attendees, the graduation ceremony was a new experience, as certificates were awarded virtually an approach that participants welcomed as innovative and inclusive.

“Cost-effectiveness analysis enables us to maximise value for money,” noted Dr. Crispus Mayora of MakSPH. “It allows decision-makers to compare interventions systematically and ensure that limited resources achieve the greatest possible benefit.”

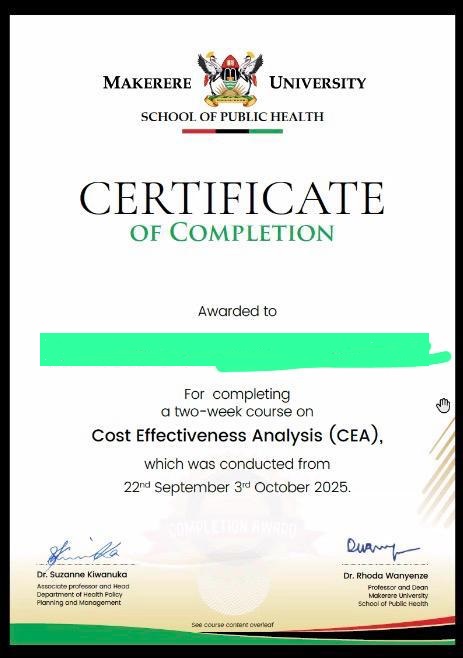

The programme aligns with Makerere University’s broader mandate to provide high-quality training that responds to national and regional development priorities. Participants who successfully complete the course receive a certificate signed by the Dean of the School of Public Health.

As the ceremony concluded, faculty encouraged continued engagement beyond the classroom. Graduates were urged to refine their project ideas and collaborate with the department in advancing research and policy discussions.

The successful completion of the first CEA short course marks an important step in building a cadre of professionals equipped to conduct rigorous economic evaluations. With plans to expand and refine the programme based on participant feedback, the HPPM department under MakSPH is positioning itself as a regional leader in health economics and policy analysis training.

Health

Uganda has until 2030 to end Open Defecation as Ntaro’s PhD Examines Kabale’s Progress

Published

6 days agoon

February 18, 2026

Silhouettes slip along narrow paths, farmers heading to their gardens, women balancing yellow jerrycans on their hips, children in oversized sweaters hurrying to school, and herders steering cattle toward open pasture, each movement part of a choreography older than memory. This is a quiet ritual in Kabale’s terraced hills, moments before the sun lifts.

The quiet procession to ahakashaka, or omukishaka, often sees figures moving quickly along familiar footpaths in the half-light, as children and adults walk with the urgency of habit. It is not a stroll but often a small, hurried run before daylight exposes what should be private.

It is February 2026, and the century-old Makerere University is celebrating its 76th Graduation Ceremony. The world paces and races toward artificial intelligence and digital revolutions. But some families still begin their day by rushing to the bushes for relief and concealment, while others engaged in economic activities such as gardening and grazing have no sanitation option other than using their surroundings to respond to the nature call!

The deadline to end open defecation is 2030. The science is settled, and the commitments are written into Sustainable Development Goal 6. Yet in parts of Kabale, only a small fraction of households is truly open defecation free.

In his PhD research, Dr. Moses Ntaro did not start with global targets or conference declarations. He began where the morning run ends, at the edge of the compounds, behind banana stems, along worn paths leading to Omukishaka. He asked whether students, equipped not with bricks but with conversation, follow-up, and persistence, could help communities replace that dash with something quieter: a door that closes.

What he found is both hopeful and unsettling. Change is possible. But dignity, like sunrise, should not require a run. And with 2030 approaching, time is no longer generous.

The Question That Would Not Let Him Go

Ntaro did not encounter open defecation as a statistic. While on foot and serving as Assistant Coordinator of Community-Based Education at Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), he learned while supervising students placed in rural communities across southwestern Uganda. They walked villages together, conducted transect walks… and they observed.

“In my role as academic coordinator,” he explains, “students always took me on transect walks within the villages to show me how high open defecation practice was. The effect was evident in the high prevalence of intestinal infections we saw in health facility records.”

The link between sanitation and disease was not theoretical but visible in clinic registers. Diarrhea, intestinal worms, recurring infections among children, and more were all visible in the clinic registers.

Nineteen years ago, in 2007, Uganda adopted Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), a strategy designed to trigger collective behavior change and eliminate open defecation. Progress, however, remained uneven. That same year, Ntaro was working as an Environmental Health Officer with the Water and Sanitation Development Facility under the Ministry of Water and Environment. He was three years away from completing his Environmental Health degree at Makerere University School of Public Health.

And so, the question emerged, to Ntaro, that, ‘If students are already embedded in these communities through COBERS placements, why are we not intentionally harnessing them to accelerate sanitation change?’

That question became his PhD.

This is a Crisis That Should No Longer Exist

Globally, more than 350 million people still practice open defecation. Sub-Saharan Africa carries a disproportionate share. SDG 6, specifically Target 6.2, commits the world to ending open defecation and ensuring universal access to safe sanitation and hygiene by 2030. It prioritizes women, girls, and vulnerable populations. It speaks of dignity, of safely managed services, and of disease prevention.

We are four years away from that deadline. And in rural Kabale District, somewhere in southwestern Uganda, Ntaro’s research found that only 3 percent of households were truly open defecation-free.

Yes, three percent. His 2025 BMC Public Health study examined 492 residents. The average age was 49. Nearly 30 percent had no formal education. Most were women, the custodians of household hygiene and child health.

The determinants of Open Defecation Free (ODF) status were deeply behavioral.

Male-headed households had higher odds of being ODF. Households with clean compounds, clean latrine holes, and consistent handwashing practices were significantly more likely to sustain sanitation improvements.

Sanitation, Ntaro realized, is not only infrastructure but also power, memory, habit, and social expectation.

“Factors associated with ODF status were not just economic,” he notes. “They were behavioral and contextual.”

Why It Feels So Wrong to Still Discuss This

Talking about open defecation in 2026 feels unsettling for three reasons. First, it feels like a failure of basic dignity.

Think of an era of global connectivity and rapid technological advancement, and hundreds of millions still lack privacy. For women and girls, this exposes them to harassment, exploitation, and fear. Sanitation is not just about disease but safety.

Second, it feels like an avoidable health crisis. One gram of feces can contain millions of viruses, bacteria, and parasites. Open defecation directly fuels cholera, typhoid, diarrhea, and environmental enteropathy, a silent contributor to child malnutrition and stunting. The science is settled, and yet the practice persists.

Third, it feels like a poverty trap. Illness leads to lost productivity; lost productivity deepens poverty, and poverty limits investment in sanitation. The cycle continues.

“Open defecation is not simply a sanitation issue,” Ntaro says. “It is linked to poverty, nutrition, and broader development.”

Testing a Different Approach

Ntaro’s doctoral thesis, “Effect of Student Community Engagement on Open Defecation-Free Status,” tested whether health profession students could effectively facilitate Community-Led Total Sanitation.

In some villages, traditional Health Extension Workers led the sanitation process. In others, trained students facilitated it under the COBERS (Community-Based Education, Research, and Service) model, which places medical trainees in community health facilities to learn through real-world practice, bridging classroom theory with primary care and public health work in rural settings.

Through this model, students led triggering, follow-ups, and community engagement. Open defecation declined. More households achieved Open Defecation Free status. And the cost per household was lower than in traditional approaches.

“Students were more effective,” Ntaro explains. “More households became open defecation-free compared to the traditional approach. And they were a cheaper human resource.”

But cost was not the real breakthrough. Presence was. Students stayed for weeks. They returned to check on latrines. They built trust. They kept coming back. Because sustainability, Ntaro argues, is not built in a single visit. It is built in repetition.

“There is a need for continued follow-ups and continued student engagement if long-term impact is to be realized.”

Change cannot be declared once and forgotten.

Behavior… and Not Just Bricks

Using the RANAS framework, Ntaro found that households that remembered to wash hands and kept latrines clean were far more likely to sustain Open Defecation Free status. In sanitation, behavior leaves evidence.

“Behavioral change interventions that empower communities,” he recommends, “such as CLTSH, should be strengthened to increase households with ODF status.”

In other words, building latrines is not enough, but communities must believe in them.

The Defense and the Countdown

On December 11, 2025, Ntaro defended his PhD. Examiners pressed him on scale and sustainability. Could student engagement be institutionalized? Could universities be embedded in district sanitation planning?

His answer was pragmatic: “Yes, but community-based education must be included in planning and budgeting.”

Four years remain to meet SDG 6.2. Four years to end open defecation and turn dignity from promise into practice. In 2026, this conversation should feel outdated. Instead, it remains urgent.

The Slow Work of Restoration

In Kabale, progress does not look dramatic. It looks like a latrine door closing firmly behind someone, a handwashing station with water and soap, a compound swept clean. It looks like a child who does not fall ill this month. Public health victories are often quiet.

As Makerere University approaches its 76th Graduation Ceremony, Dr. Ntaro Moses stands among its PhD graduands not with theory alone, but with evidence that change can be accelerated by reimagining who leads it. Students, he shows, are not only learners. They are the workforce, facilitators, and bridges between policy and path.

The hills of Kabale still wake under mist. But in more compounds now, privacy exists where bushes once stood open. Dignity is not restored in headlines, but one household at a time.

And with 2030 approaching, Ntaro’s work leaves a final, unavoidable question: if we already know how to end open defecation, if we already have the tools, the evidence, and the people, what, exactly, are we waiting for?

— Makerere University School of Public Health Communications Office, Graduation Profiles Series, 76th Graduation Ceremony

Health

Olivia Nakisita and the Quiet Urgency of Adolescent Refugee Health

Published

6 days agoon

February 18, 2026

Kampala wakes early, but for some girls, the day begins already heavy. In Uganda, nearly three-quarters of the population is under 30, growing up happens fast, and often without protection. One in four Ugandan girls aged 15–19 has already begun childbearing, giving Uganda the highest teenage pregnancy rate in East Africa.

Layered onto this is displacement. The country hosts about 1.7 million refugees, many living in cities like Kampala, where survival depends on navigating systems not designed with them in mind. Also, nationally, 1.4 million people live with HIV, and 70 per cent of new infections among young people occur in adolescent girls, a reminder that vulnerability is rarely singular. When COVID-19 shut the country down, the consequences were immediate, with pregnancies among girls aged 15–19 rising by 25.5 per cent, while pregnancies among girls aged 10–14 surged by 366 per cent.

The numbers tell a story of youth, risk, and quiet urgency. But they do not tell it all. For years, Olivia Nakisita, a public health researcher,has followed how adolescent girls, many of them refugees, navigate pregnancy in Kampala: how far they must travel for care, how early they arrive or delay, and how often services that exist fail to meet them where they are. Her work lives at the uneasy intersection of policy and lived reality, where access does not always translate into care.

February 25th 2026, is the day that her work on whether urban health systems are truly ready for the youngest mothers they now serve will bring her to Freedom Square at Makerere University, where she will graduate with a PhD in Public Health.

Her doctoral journey, focused on maternal health services for adolescent refugees in urban Uganda, has unfolded at the intersection of scholarship, community service, and the daily realities of young girls navigating pregnancy far from home.

The Work That Came Before the Question

Long before she began writing a PhD proposal, Olivia Nakisita was already immersed in adolescent health. As a Research Associate in the Department of Community Health and Behavioral Sciences at Makerere University’s School of Public Health, she taught graduate and undergraduate students, supervised Master’s research, and worked closely with communities. Beyond the university, she led New Life Adolescent and Youth Organization (NAYO), a women-led organisation she founded in 2021 to strengthen access to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) information and services for adolescents and young people.

It was through this community work that a troubling pattern began to surface.

“During our community service,” she explains, “we noted increasing teenage pregnancies, and we also noted challenges with access to maternal health services by teenage pregnant girls.”

Among those girls were adolescents living as urban refugees in Kampala, young, displaced, often poor, and navigating pregnancy in a city not designed with them in mind.

For Nakisita, the concern deepened through her academic training in Public Health Disaster Management, one such programme that prepares multidisciplinary professionals with the technical expertise and leadership competencies required to plan for, mitigate, respond to, and recover from complex disasters through a public health lens. This programme sharpened Nakisita’s interest in how displaced populations survive within complex urban systems. Uganda’s integrated health model, where refugees and host communities are expected to use the same facilities, appears equitable on paper. In practice, it can be unforgiving.

“I got interested in understanding how these refugees who get pregnant manage to navigate the complexities of integration in host societies like Kampala,” she says. “This was driven by the desire to address their needs and to inform and evaluate existing refugee health policies.”

That desire became the foundation of her PhD.

Asking Hard Questions in a Crowded City

Her doctoral research, “Maternal Health Services for Adolescent Refugees in Urban Settings in Uganda: Access, Utilisation, and Health Facility Readiness,” was conducted in Kampala between November 2023 and August 2024. It combined quantitative surveys with qualitative interviews, engaging 637 adolescent refugees aged 10–19 years, alongside health workers and facility assessments.

Her findings showed high perceived access to maternal health services. Clinics existed. Services were available. Yet utilisation, particularly of antenatal care (ANC), lagged. “About three-quarters of the girls attended at least one antenatal visit,” she explains, “but only about four in ten attended in the first trimester.”

And that gap matters. Public health research shows that early and regular antenatal care allows health workers to detect high-risk pregnancies, initiate supplements such as iron and folic acid, monitor fetal development, and provide psychosocial support. Without it, risks compound silently.

By contrast, her study found that facility-based deliveries were remarkably high, with nearly all adolescent refugees (98.3%) giving birth in health facilities, suggesting that the system was reachable, but uneven.

Where the System Falls Short

Her research went beyond utilisation to examine whether health facilities were actually ready to serve adolescent refugees.

Findings show that lower-level health centres in Kampala were moderately prepared to offer adolescent-friendly maternal health services. Some staff were trained. Some spaces existed. Despite this, critical gaps remained. For instance, facilities lacked essential equipment and supplies. Non-provider staff were often untrained. Separate, private spaces for adolescents were limited. Language barriers complicated care. Overcrowding strained already stretched health workers.

In her qualitative interviews, health workers expressed empathy and willingness to help. Many relied on peer educators and community health workers to reach adolescent refugees. But good intentions were not enough.

“They recommended training of healthcare workers, translators for refugees, and improvement in the availability of essential drugs, supplies, and equipment,” Nakisita notes.

She notes that readiness is not just about infrastructure but about the people, preparation, and priorities.

Research with an Emotional Cost

For Nakisita, working with adolescent refugees required care, not only methodologically, but emotionally.

Finding participants in Kampala was itself a challenge. Unlike settlement settings, urban refugees are dispersed, often invisible. Ethical considerations were constant. Adolescents who had given birth were legally considered emancipated minors, but their vulnerability remained.

Though the thesis focused on systems rather than personal narratives, Nakisita’s earlier work with adolescents informed every decision she made. It shaped how she framed questions, interpreted data, and weighed policy implications. This was not detached research, but careful, deliberate, and grounded.

The Scholar Formed by Continuity

Nakisita’s PhD sits atop more than 18 years of experience in training, research, and community service. She is an alumna of Makerere College School (UCE), 1996 and Greenhill Academy Secondary School (UACE), 1998, a long journey through Uganda’s education system before her Diploma in Project Planning and Management at Makerere University completed in early 2000s.

She would later return eight years later to Makerere University for her Bachelor’s degree in Social Sciences and a Master’s in Public Health Disaster Management, and now a PhD in Public Health.

Her academic rigor is reflected in extensive training across SRHR, impact evaluation, research methods, ethics, disaster resilience, and humanitarian health. She has presented at regional and international conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals on adolescent health, refugee maternal care, gender-based violence, and health systems readiness.

As a PhD student, she supervised three Master’s students to completion, with another currently progressing, quietly extending her influence through mentorship.

When Evidence Demands Action

If policymakers were to act on one lesson from her research, Nakisita says; “Emphasis should be given to maternal health services for adolescents.” “They are high-risk mothers,” she adds.

Her findings call for targeted community-based interventions, outreaches, home visits, and financial support for adolescents who cannot afford prescribed drugs, delivery requirements, or critical tests like ultrasound scans.

They also call for health systems to move beyond one-size-fits-all models, recognising that age, displacement, and poverty intersect to shape how care is accessed and experienced.

Now that her PhD is complete, Nakisita plans to translate research into action. Several papers from her study have already been published. A policy brief is planned to influence decision-making in urban and humanitarian health settings.

When asked what she would say directly to adolescent refugee girls navigating pregnancy in unfamiliar cities, her response is simple and direct.

“If it happens,” she says, “as soon as you find out, go to the nearest health facility and seek care. Always return for the visits as asked by the health worker. Ensure that you deliver in a health facility with a skilled health worker.”

Arrival, Without Illusion

When Dr. Olivia Nakisita steps onto the graduation stage at Freedom Square, applause will follow. But the true significance of that moment lies in health facilities still struggling to adapt; in adolescent refugees whose pregnancies unfold quietly in rented rooms and crowded neighborhoods; in policies waiting to be sharpened by evidence.

Her scholarship does not promise quick fixes but offers clarity.

Among the PhDs conferred at Makerere University’s 76th graduation, her work reminds us that some research does not begin in libraries and does not end with theses. It lives on in the slow, necessary work of making health systems see those they have long overlooked.

— Makerere University School of Public Health Communications Office, Graduation Profiles Series, 76th Graduation Ceremony

Trending

-

Health6 days ago

Health6 days agoUganda has until 2030 to end Open Defecation as Ntaro’s PhD Examines Kabale’s Progress

-

Humanities & Social Sciences1 day ago

Humanities & Social Sciences1 day agoMeet Najjuka Whitney, The Girl Who Missed Law and Found Her Voice

-

Agriculture & Environment4 days ago

Agriculture & Environment4 days agoUganda Martyrs Namugongo Students Turn Organic Waste into Soap in an Innovative School Project on Sustainable Waste Management

-

General6 days ago

General6 days agoMastercard Foundation Scholars embrace and honour their rich cultural diversity

-

Health2 weeks ago

Health2 weeks agoCall for Applications: Short Course in Molecular Diagnostics March 2026