Health

Mak Researchers Design National Drowning Prevention Strategy

Published

5 years agoon

By Joseph Odoi

Makerere University researchers under Trauma, Injuries and Disability (TRIAD) Unit) have designed a national drowning prevention strategy. This strategy comes at a time when there is sky rocketing cases of drowning in Africa.

Globally, drowning is the third leading cause of unintentional injury death; accounting for 7% of all injuries. Over 90% of the estimated 322,000 annual global drowning deaths occur in low-and middle-income countries.

Although the burden of drowning is believed to be highest in the WHO-African region, data collection and surveillance for drowning in African countries is limited.

In bid to contribute to data driven interventions, Makerere University researchers carried out a study aimed at establishing the availability of drowning data in district-level sources and understanding the reporting of and record keeping on drowning in Uganda.

As part of the study titled: Drowning in Uganda; examining data from administrative sources, researchers engaged various health stakeholders who shared their experiences about drowning and how it can be prevented in communities.

It is upon that background that scholars designed a contextual appropriate strategy for drowning prevention in Uganda under the project titled; Drowning in Uganda; examining data from administrative sources.

According to the researchers, this drowning strategy is first ever in Uganda. ‘’it will be a national document that will guide all the efforts on drowning prevention in the country; and will avoid non-coordinated activities aimed at prevention of drowning. the strategy will also provide for monitoring and evaluation of all activities and interventions for drowning prevention in the country since there will be a government lead agency tasked with this responsibility’ ’explained Mr. Fredrick Oporia who is part of the study team

STRATEGIES TO PREVENT DROWNING

In this study published on semantics scholar among other journals, the researchers came up with the following strategies to counter drowning;

• Setting and enforcing safe boating regulations. • Providing incentives that encourage adherence to boating regulations related to not overloading transport boats and increasing enforcement of boating regulations. • Ensuring boats are fit for purpose and increasing regular inspection of the seaworthiness of boats. • Improving detection and dissemination of information about the weather. • Supporting increased availability and use of lifejackets through subsidy, lifejacket loaner programs, and free lifejacket distribution programs. • Increasing sensitization about safe boating practices, the importance of wearing lifejackets, and limiting alcohol and illicit drug use when boating. Community members, especially children, are vulnerable to drowning in unsafe water sources such as ditches, latrines, wells, and dams. Potential interventions could include: • Modifying access to wells and dams to prevent children or adults from falling in. • Installing boreholes and pumps to enable community members to draw water safely.

Providing safe rescue and resuscitation training to community members and conducting refresher trainings. • Developing and providing low-cost rescue equipment such as boat fenders (rubber and ropes tied to boat on all sides that can assist in the immediate rescue of individuals) and buoyant throwing aids.

To enable ongoing design, implementation, and evaluation of drowning prevention efforts, the researchers note that it is essential to collect data on drowning incidents. Reporting of and record keeping on drowning in Uganda should also be improve according to the researchers namely; Tessa Clemens, Frederick Oporia, Erin M Parker, Merissa, A Yellman, Michael F Ballesteros and Olive Kobusingye

Other Potential interventions highlighted by the researchers include: • Providing records officers with proper training, equipment, and appropriate storage facilities. • Sensitizing the public on the importance of reporting all drowning cases to authorities.

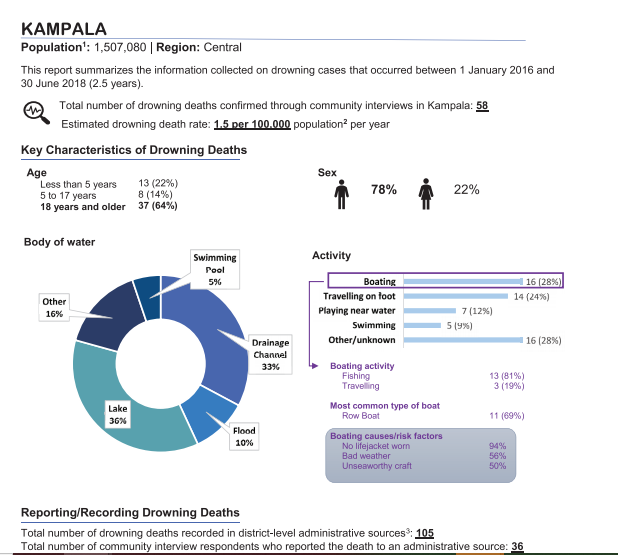

As part of their study findings, the researchers noted that; A total of 1435 fatal and non-fatal drowning cases were recorded; 1009 (70%) in lakeside districts and 426 (30%) in non-lakeside districts.

Of 1292 fatal cases, 1041 (81%) were identified in only one source. After deduplication, 1283 (89% of recorded cases; 1160 fatal, 123 non-fatal) unique drowning cases remained. Data completeness varied by source and variable.

On demographics, fatal victims were predominantly male (85%), and the average age was 24 years. In lakeside districts, 81% of fatal cases with a known activity at the time of drowning involved boating.

What were people doing when they drowned?

Activity at the time of drowning in lakeside districts and non-lakeside districts

• Overall, boating was by far the most common activity that people were engaged in at the time of the drowning incident.

• Other common activities were collecting water/watering cattle and travelling on foot.

• The most common activities that people engaged in prior to drowning were similar in lakeside and non-lakeside districts. However, in non-lakeside districts, more drowning deaths occurred as a result of collecting water or watering cattle than as a result of boating in those districts.

• Almost half (48%) of all drownings occurred while the person was engaged in an occupational activity.

Of the 1,063 people who died from boating-related drowning or suffered a severe boating related drowning incident but survived, 1,007 (95%) were not wearing a lifejacket at the time of the incident.

Bathing in water bodies: Study participants indicated that drowning sometimes occurs when people are bathing in lakes, ponds, swamps, and valley dams. People can unexpectedly slip into deep water from shallower areas or rocks.

Crossing flooded rivers and streams:

Attempting to cross flooded rivers and streams during the rainy season was another cause of drowning identified by study participants.

“Currently, people cross from makeshift bridges such as that of round poles. When the river overflows, it covers them. So, you can’t see them; so, you just start guessing: ‘the pole might be here or there’ and in case your guess is wrong, you automatically drown and you will be gone.” an Interview respondent in Kabale district explained

Delayed rescue attempts: Study participants identified the importance of timely rescue and resuscitation to prevent death from drowning. However, they also indicated that community members lack knowledge on how to rescue someone who is drowning.

Alcohol use: Several participants identified alcohol use as a key risk factor for drowning. Participants stated that alcohol use is common, especially in fishing communities. “We have a problem with alcoholism. Many of our colleagues go to the waters when their minds are a bit twisted by the alcohol and on some occasions, this has caused accidents and some of them have drowned just like that.” – Interview respondent, Nakasongola district.

When asked on strategies of preventing drowning, participants suggested the following strategies for preventing drowning:

• Provide affordable and high-quality lifejackets to all water transport users and fishing communities. • Increase sensitization of fishermen and all water transport users on the importance of using lifejackets and avoiding alcohol while boating. • Provide subsidies for large and motorized boats that can be used for safe water travel and fishing to replace small and low-quality boats that are currently in use.

Inspect boats regularly to ensure they are in good travelling condition. • Recruit and deploy more marine police units on all major water bodies to enhance security and quick response to drowning incidents. • Install boat fenders (rubber and ropes tied to boat on all sides) to assist with the immediate rescue of individuals who are involved in a drowning incident. • Provide frequent and safe ferry services to enable water travellers access to safe transportation across rivers and lakes. • Avoid fishing during the moonlight periods to minimize hippopotamus attacks which are more frequent at that time.

“I think these fishermen really need lifejackets for their work and also need to be sensitized on how to manage the engine of the boats that they use for their work. In most cases, these men just learn how to use these boats without having been trained first.” – Interview respondent, Rakai district. Swimming and basic rescue skills said

Moving forward, the researchers recommend that since; drowning is a multisectoral issue, and all stakeholders (local and national government, water transport, water sport, education, fishing, health, and law enforcement) should coordinate to develop a national water safety strategy and action plan.

MORE ABOUT THE STUDY

The study was conducted in 60 districts of Uganda for a period of 2.5 years (from January 1st, 2016 to June 30th, 2018). In the first phase, records concerning 1,435 drowning cases were found in the 60 study districts.

In the second phase, a total of 2,066 drowning cases were identified in 14 districts by community health workers and confirmed through individual interviews with witnesses/family members/friends and survivors of drowning. This work was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies through the CDC Foundation

You may like

-

Botswana Delegation Visits Makerere’s Public Investment Management Centre to Study Sustainable Training Model

-

Makerere University commemorates 13 transformative years of partnership with Mastercard Foundation

-

200 UVTAB students graduate: CEES emphasizes Skills, Integrity and Community Impact

-

Mak News Magazine: February 2026

-

Celebrating Academic Excellence: CoBAMS Presents 975 Graduands at Mak 76th Graduation Ceremony

-

Makerere’s 76th Graduation Ceremony: CHS showcases research strength with 26 PhD Graduates

Health

Makerere’s 76th Graduation Ceremony: CHS showcases research strength with 26 PhD Graduates

Published

6 days agoon

February 26, 2026By

Zaam Ssali

The second day of the Makerere University 76th Graduation Ceremony, held on Wednesday 25th February, marked another proud moment as the institution continues its tradition of academic excellence and national service. Graduands were presented for conferment of degrees and award of diplomas from the College of Health Sciences (CHS), College of Natural Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Animal Resources and Biosecurity and School of Public Health.

The College of Health Sciences presented a total of 746 graduands for conferment of degrees including 26 PhD, 293 Masters, 425 Bachelors and 2 Diplomas. This is a testament to CHS and Makerere University’s contribution in training skilled health professionals and strengthening Uganda’s health systems through education, innovation and research.

Speaking to the congregation, Professor Barnabas Nawangwe – Vice Chancellor, Makerere University welcomed everyone to Day 2 of Makerere University’s 76th Graduation. He congratulated the 9,295 graduands comprising 4,262 (46%) female graduates and 5,033 (54%) male graduands who will be awarded degrees and diplomas through the graduation week; 213 graduands are PhD recipients. He commended the efforts of staff, parents, and sponsors in supporting the students’ journeys.

He reminded the congregation that outstanding researchers were honored on Day 1 of the graduation for excellence in scholarly work and impactful publications, reaffirming the University’ commitment to research productivity and academic distinction. In addition, the Innovation Commercialization Award was also presented, highlighting Makerere’s focus on turning research into practical solutions that address real-world challenges and drive national development.

The Vice Chancellor highlighted the history of the College established in 1924 cognizant of its impact on Uganda’s Health sector and beyond. He said, ‘As the College enters its second century, it is strengthening specialist training to address increasingly complex health challenges’. CHS has introduced fellowship programmes to equip physicians with advanced expertise which are useful in transforming health systems across Uganda and the region. In 2025 alone, 16 fellows graduated in Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, with additional fellowships underway in Newborn Health, Interventional Radiology, Emergency Care Medicine, and Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine.

Professor Nawangwe also noted the progression of one of the centres of excellence at CHS, the Makerere University Lung Institute (MLI) established a decade ago to address the growing burden of lung disease in Uganda. He said, ‘today, the MLI serves 6,000 patients annually, shapes national policy and has embarked on construction of a new building, signalling a renewed commitment to advancing respiratory health in Uganda and beyond’.

He also reminded the congregation that CHS continues its centennial celebrations, including the upcoming Alumni Dinner Gala on March 6th 2026 to raise funds for refurbishing the iconic Davis Lecture Theatre, culminating in the unveiling of a Centennial Monument later this year.

Professor Nawangwe applauded the steady advancement of Makerere University into a research-led institution, generating knowledge that drives communities, strengthens industries, and advances national transformation.

Professor Maggie Kigozi was the commencement speaker for Day 2. Professor Kigozi, a distinguished alumna reflected on how her time at Makerere University shaped her life, career, and values, recalling her graduation in 1976 during a period of national uncertainty. Forced to leave Uganda soon after with little more than her education and determination, she noted that her Makerere training opened doors across the region, enabling her to serve in leading health institutions in Zambia, Kenya, and Uganda. Addressing the graduands, she emphasized that their Makerere education remains a powerful passport to opportunity and carries with it the responsibility to uphold excellence and integrity wherever they serve.

She urged graduates in the health and life sciences to handle the power of their profession with humility, compassion, and responsibility, reminding them that behind every patient, case, or experiment lies a life deserving dignity. Beyond clinical expertise, she encouraged them to develop business and financial skills to build sustainable health services and create opportunities for others. She also reassured them that failure is part of growth, noting that resilience, continuous learning, and balance in life are essential to meaningful success as they step forward as ambassadors of the Makerere legacy.

Delivering a speech on behalf of the First Lady and Minister of Education and Sports, Janet Kataha Museveni, the State Minister for Primary Education, Hon. Dr. Joyce Moriku Kaducu, said the Government had deliberately deepened investment in higher education to position universities as drivers of national development.

Hon. Kaducu described the establishment of the Makerere University Research and Innovation Fund (RIF) as a major milestone, noting that it supports high-impact research aligned to national priorities and has enabled thousands of researchers to deliver practical solutions benefiting communities across Uganda. She also highlighted Parliament’s approval of a 162 million US dollar concessional loan from the Korea EXIM Bank to upgrade science, technology and innovation infrastructure at Makerere University, including modern laboratories, smart classrooms and advanced facilities for engineering and health sciences, to better prepare students for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

The Minister announced plans to construct a national stadium at Makerere and other higher education institutions to promote sports development and talent identification. She reiterated the directive for all universities to fully implement Competence-Based Education and Training by July 2027, urging Makerere to lead curriculum reform, staff training and infrastructure development while ensuring satellite campuses meet full accreditation and uphold academic standards, transparency and accountability.

Addressing graduates, Hon. Kaducu encouraged them to become job creators in sectors such as agriculture, infrastructure, healthcare and education, and to leverage opportunities like the Parish Development Model for entrepreneurship. She commended Makerere’s leadership and partners and congratulated the Class of 2026 on their achievement.

In his address to the congregation, Dr. Crispus Kiyonga – Chancellor, Makerere University congratulated graduands upon making it to the 76th Graduation Ceremony of Makerere University. He described their achievement as a milestone in both personal growth and national development, urging them to apply their knowledge creatively to benefit society. He acknowledged the contribution of academic staff, administrators, the University Council, and expressed gratitude to the Government of Uganda and President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni for continued support.

Dr. Kiyonga called on the university community to strengthen research, expand private sector partnerships, and leverage technology to address Uganda’s development challenges. Emphasising research as central to national progress, Dr. Kiyonga noted the Government’s UGX 30 billion investment annually in the Makerere University Research and Innovation Fund (MakRIF) and praised the Science, Technology and Innovation Secretariat, Office of the President for supporting initiatives at the University advancing homegrown solutions to national challenges. He also highlighted a strengthened partnership with the Korean government, securing a USD 162 million loan from the Korea Exim Bank to boost infrastructure and staff capacity.

While acknowledging limited formal employment opportunities, he encouraged graduates to innovate and create jobs. He further commended the university’s digitalization efforts and outlined four priorities: increased research funding, private sector collaboration, community engagement, and effective use of technology.

During the 76th graduation ceremony running from the 24th -27th February, 2026, a total of 9,295 graduands will be awarded degrees and diplomas in various disciplines. Of these, 213 will receive PhDs, 2,503 Masters Degrees, 206 postgraduate Diplomas, 6343 Bachelor’s Degrees and 30 Diplomas. 46% of the graduands are female and 54% are male.

Health

MakSPH Environmental Health Graduates Trained to Prevent Disease at Its Source

Published

1 week agoon

February 24, 2026

In most health systems, attention turns to illness after it appears in clinics and hospitals. Environmental Health works earlier, often invisibly, by preventing disease before treatment becomes necessary. At Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH), this preventive philosophy shapes the training of students learning to manage health risks at their source, through sanitation systems, safer environments, community engagement, and evidence-based public health action.

This year, as MakSPH presents 29 graduands approved by the Makerere University Senate for the award of the Bachelor of Environmental Health Science (BEHS) degree, four outstanding students graduate with first-class honours. Their journeys, shaped by different personal histories and professional ambitions, provide a clear view of how the School prepares practitioners whose work begins long before patients reach health facilities. Through academic training, field practice, research exposure, and leadership experience, the programme equips graduates to address the environmental and social conditions that determine health outcomes across communities.

Environmental health occupies a distinctive position within public health practice. Rather than focusing primarily on diagnosis or treatment, practitioners work at the intersection of science, policy, and society, addressing risks linked to water and sanitation, food safety, occupational health, climate change, and urbanisation. The discipline demands technical competence alongside communication, systems thinking, and community engagement, capabilities that increasingly define modern public health leadership.

The journeys of Nakulima Bushirah, graduating with a CGPA of 4.58 on February 25, 2026, Mujurani Alphersiiru with 4.44, and Cherop Eric with 4.41, alongside Phillip Acaye, the cohort’s overall best student with a CGPA of 4.63, demonstrate how MakSPH shapes students from varied beginnings into professionals grounded in prevention. Their paths reveal a shared formation that links classroom learning with real-world health challenges and prepares graduates to prevent disease before it occurs.

Bushirah Nakulima’s Turn Toward Prevention

For Bushirah Nakulima, environmental health began during a period of uncertainty. The COVID-19 pandemic repeatedly disrupted her Bachelor of Pharmacy studies at Kampala International University, prompting reflection about the kind of health professional she wanted to become. A conversation with a family friend working in preventive health introduced an alternative path, one focused not on treating illness after onset but on preventing it altogether.

“When I applied to Makerere University in 2022, I was considering two career paths,” she recalled. “I prayed to Allah to guide me toward the best one. When I was admitted to the Bachelor of Environmental Health Science, I accepted it wholeheartedly, and I came to appreciate it even more as I studied.”

Her academic foundation had already demonstrated consistency. She progressed from Melody Junior School in Nansana, where she obtained aggregate eight in 2010, to Shuhada’e Islamic School in Nyamitanga, completing O-Level with 25 aggregates in 2016 and A-Level with 10 points in 2018. Pharmacy initially appeared the logical continuation, yet environmental health offered something broader in scale and impact.

“Environmental Health offered an opportunity to prevent illness and suffering before it occurs,” she explained. “It allows a single intervention, such as WASH or health education, to protect many people at once, and it provides flexibility to work across diverse environments. It offered freedom to operate in various settings, which truly connects with my personality since I love exploration.”

At MakSPH, classroom concepts quickly translated into practice. During her internship at Mukono Municipal Council, she conducted school health education sessions, participated in inspections of markets and abattoirs, and engaged communities facing sanitation challenges. Field exposure deepened her understanding of how environmental conditions directly shape disease patterns, reinforcing prevention as both a scientific and social responsibility.

Leadership further expanded her training. Serving as the 90th Female Guild Representative Councillor (GRC), she represented the School of Public Health in the Student Guild structure, facilitating engagement between students and School leadership on academic and welfare matters. The role strengthened her capacity for representation, negotiation, and collaborative problem-solving, skills central to public health practice, where advocacy and systems engagement are inseparable from technical expertise.

Graduating with a CGPA of 4.58, Bushirah’s research examined roadside vendors’ exposure to air pollution in Kampala, reflecting growing concern about occupational and urban environmental risks. She now plans to pursue advanced training in public health, building on MakSPH’s emphasis on evidence-driven and community-centred practice.

Cherop Eric’s Return to the Classroom

Eric Cherop’s journey into environmental health began not in lecture halls but in community service. Raised in Kapchorwa District, he was shaped by economic hardship and resilience, experiences that informed his commitment to community well-being.

He completed his Primary Leaving Examinations at Chema Primary School, a Universal Primary Education institution, attaining 24 aggregates in 2008. He later joined Sipi Secondary School, where he obtained 37 aggregates at Uganda Certificate of Education in 2012 and continued at the same school for A-Level, earning 8 points at Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education in 2014.

After earning a Diploma in environmental health sciences from Mbale School of Hygiene between 2015 and 2017, he entered public service as an Environmental Health Officer and Community Field Facilitator with Kapchorwa District Local Government. His work included sanitation campaigns, climate resilience initiatives, nutrition education, and household behaviour change programmes. Over time, field experience revealed the limits of practice without deeper theoretical grounding.

“I wanted to understand not only what works in communities, but why it works,” he explains. Enrolling in the BEHS programme at MakSPH in 2022 allowed him to connect practical experience with analytical training. Coursework strengthened competencies in environmental risk assessment, participatory engagement, and data-driven planning. Mentorship reshaped how he interpreted evidence.

“My lecturers helped me move beyond seeing data as numbers,” he said. “I learned to see it as evidence that guides decisions and improves accountability.” Graduating with a CGPA of 4.41, Eric now aims to advance evidence-driven leadership at the intersection of climate change, nutrition, and environmental health, ensuring interventions remain grounded in community realities.

Mujurani Alphersiiru’s Path into Environmental Health

For Mujurani Alphersiiru, Environmental Health arrived at an unexpected moment, when his academic future appeared uncertain. Financial pressures had begun to threaten the continuation of his Bachelor of Nursing Science studies at Kampala International University Western Campus, raising the real possibility that his university education might end prematurely. The turning point came when the government district quota admission list was released, offering him placement at Makerere University under Bunyangabu District and opening an alternative academic pathway he had not previously considered.

At the time, environmental health was unfamiliar to him. “I didn’t know what environmental health was,” he recalls. “But I celebrated because I had reached my dream university.” Orientation sessions and early coursework gradually reframed that uncertainty, revealing a discipline grounded in prevention, systems thinking, and public health policy. What began as an unexpected opportunity soon developed into a clear professional direction.

Serving as class president and 90th Male GRC for the School with Nakulima Bushirah, Mujurani organised student activities, mobilised community outreach initiatives, and advocated for improved learning environments. Balancing leadership responsibilities with academic performance required deliberate discipline and time management.

His educational foundation began at St. Augustine Butiiti Demonstration Primary School in Kyenjojo, where he scored 12 aggregates in 2014. He later attended Pride Secondary School in Mityana, attaining 25 aggregates at O-Level in 2018, before proceeding to Kibiito Secondary School in Bunyangabu, where he obtained 13 points at A-Level in 2021, performance that earned him government sponsorship for university education. At MakSPH, faculty mentorship further strengthened both his academic rigour and commitment to public service.

“Government sponsorship meant responsibility,” Mujurani said. “I had to plan my time carefully while remaining active in school programmes.” Graduating with a CGPA of 4.44, his interests now centre on governance and accountability within health systems, particularly strengthening the implementation of public health policies.

Training Prevention Professionals

Taken together, the three journeys demonstrate how MakSPH’s Environmental Health training converts diverse personal backgrounds into a shared professional orientation centred on prevention. Through interdisciplinary coursework, field placements, research mentorship, and leadership opportunities, students develop competencies that extend beyond technical knowledge to include systems thinking and public engagement.

The BEHS programme, established in 2000 within MakSPH’s Department of Disease Control and Environmental Health, remains the School’s only undergraduate degree and has trained more than 1,000 graduates who now serve across government institutions, non-governmental organisations, academia, and international health programmes. Its continued evolution reflects growing recognition that strengthening health systems requires professionals capable of addressing environmental risks before illness occurs.

The achievements of this year’s graduates, therefore, represent more than academic distinction. They reflect a model of training designed to prepare professionals whose work reduces the need for treatment by preventing disease at its source, reinforcing MakSPH’s role in shaping Uganda’s environmental health workforce.

Health

Philliph Acaye and the Making of Uganda’s Environmental Health Workforce

Published

1 week agoon

February 24, 2026

As Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH) presents 29 graduands on February 25, 2026, at Makerere University’s 76th Graduation Ceremony, for the conferment of the Bachelor of Environmental Health Science (BEHS) degree, the journey of the cohort’s best student provides a compelling window into both individual resilience and institutional impact. Philliph Acaye, graduating with a CGPA of 4.63, represents more than academic distinction. His story reflects the lived realities that shape many public health professionals in Uganda and shows how rigorous training can transform experience into leadership within health systems.

Education Shaped by Conflict

Acaye was born on October 2, 1993, in Wangduku Village, Palenga Parish, Pajule Sub-County, Pader District in northern Uganda, a region deeply affected by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) insurgency in the early 2000s, where education and security often existed in constant tension. As a child, schooling unfolded alongside displacement and uncertainty, conditions that shaped an entire generation growing up during the conflict.

“Around 2002, before we had fully moved into the IDP camps, we often ran with our parents whenever there were LRA attacks,” he recalls. “But on several occasions, they caught us unaware. During one of the attacks, they abducted me and moved with me for close to seven kilometres, from Wangduku to Pajule Trading Centre in Pader. At first, they said I was too young to be moved with. I was around nine or ten years old. Later, I understood that someone among them personally knew my father and did not want me taken, so he used my age as the reason, and they left me behind.”

He narrates that several relatives and neighbours, including some of his childhood friends, were not spared, among them an uncle whose whereabouts remain unknown to this day. “If they had gone with me,” Acaye reflects quietly, “I could be dead, or I might not have studied.” The remark sits deep and places his graduation in context, not simply as personal success, but as the outcome of persistence through years when conflict repeatedly disrupted education across northern Uganda.

Between 2002 and 2006, his schooling continued inside Pajule Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) Camp, where families lived in overcrowded settlements and depended largely on relief food. Learning environments were unstable, teachers travelled under risk, and lessons were frequently interrupted by insecurity. Even within the camps, attacks remained possible. Education progressed slowly, but it continued, sustained by families and teachers who insisted that schooling remained essential despite uncertainty.

When communities gradually returned home, Acaye rebuilt his academic track record step by step. He completed Primary Leaving Examinations in 2007 with an aggregate of 19 and was the best pupil at Wangduku Primary School, at a time when enrolment remained low because many families feared returning to villages. He proceeded to Pajule Senior Secondary School, completing O-Level in 2011 with 31 aggregates, and later obtained 10 points at A-Level in 2013 from Kitgum High School.

However, his progression was shaped by consistent recovery after disruption, supported by relatives, teachers, community mentors, and educational assistance from Invisible Children, a post-LRA conflict recovery NGO led locally by Ms. Laker Jolly Okot, which supported his A-Level education.

Professional direction emerged during his training at the Mbale School of Hygiene, where he pursued a Diploma in Environmental Health Science from 2014 to 2016 and graduated with a strong CGPA of 4.4. The diploma opened immediate employment opportunities in community and humanitarian health settings back home, followed by service in local government. Today, he works as a Health Inspector in Kitgum District Local Government, implementing sanitation monitoring, infection prevention activities, and community health interventions. Practical experience strengthened his understanding of public health challenges but also revealed limits in technical depth that he felt required further training.

Training the Public Health Professional

His admission to MakSPH in 2022 through the government diploma-entry sponsorship scheme represented a deliberate academic decision rather than a career reset. He sought broader analytical skills and a stronger grounding in environmental health systems, particularly in areas of surveillance, planning, and evidence-based decision-making.

“I realised some technical aspects were not fully covered at the diploma level. I wanted to understand public health beyond implementation and learn how decisions are justified scientifically,” Acaye explained.

The sponsorship, he observed, transformed that ambition into possibility and remains central to how he understands his academic journey at Makerere University. “I am grateful to the Makerere University selection committee, the MakSPH selection committee, and the Government of Uganda for this opportunity. Opportunities like this are not guaranteed, and I recognise the trust placed in me to undertake and complete the three-year BEHS programme.”

The transition into university study was not seamless, though. His admission had come earlier than planned, and he began coursework without formal study leave while still tied to workplace obligations in Kitgum. Sustained support from district leadership, particularly Dr. Okello Henry Otto, the District Health Officer, eventually enabled him to secure study leave and concentrate fully on academic work. Now with stability came rapid academic improvement, supported by peer learning, faculty mentorship, and a strong curriculum that emphasised analytical reasoning alongside applied practice.

Acaye attributes his transformation to the programme’s academic culture rather than individual brilliance. “The programme helped me realise that what I was doing before was only a surface understanding,” he argued. “I learned to approach public health more deeply.” Exposure to research methods, he revealed, reshaped how he interpreted field experience and encouraged him to submit an abstract to an international academic conference, marking his transition from practitioner to emerging researcher.

For Mr. Abdallah Ali Halage, the MakSPH Coordinator of the BEHS programme, such outcomes reflect intentional design rather than coincidence. He noted that student success is rooted in a training philosophy that combines technical instruction with professional discipline from the moment students enter the programme. According to him, orientation focuses not only on coursework but also on expectations of conduct, independence, and responsibility. “When students join, we brief them on how seriously they must approach their academic journey,” he said. “That grounding helps shape their performance over time.”

Mr. Halage argued that while some high-performing students enter through diploma schemes, achievement ultimately depends on commitment and effort rather than background. He cited Acaye’s consistent curiosity and self-motivation as defining traits, noting that strong academic results tend to follow students who actively engage with the learning process.

“I congratulate Philliph and his colleagues upon attaining first-class honours and performing very well academically. Philliph has been hardworking and self-motivated. He has consistently shown a strong interest in his studies, and that commitment has helped him achieve this result. He has been a very good student,” Mr. Halage attested.

He added that the achievement reflects a broader culture within the programme. “Our students are disciplined and independent. Their commitment, together with support from the School management, the College and University leadership, has contributed greatly to their success.”

From Individual Achievement to Institutional Impact

The broader significance of Acaye’s achievement becomes clearer when placed within the evolution of the BEHS programme itself. Established in 2000 within MakSPH’s Department of Disease Control and Environmental Health (DCEH), the programme remains the School’s sole undergraduate degree and was among the earliest environmental health bachelor’s programmes in East Africa. In more than two decades, it has produced over 1,000 graduates, expanding professional capacity beyond diploma-level training and strengthening Uganda and the region’s environmental health workforce across government, non-governmental organisations, educational institutions, and points of entry such as airports and border services.

Mr. Halage explained that the programme helped redefine career pathways within the government of Uganda’s public service structures by introducing degree-level expertise into environmental health roles. Graduates now serve as Environmental Health Officers, Senior Environmental Health Officers, and technical specialists contributing to policy implementation and service delivery across multiple sectors. The academic pathway has also expanded vertically, with postgraduate training opportunities at MakSPH currently enabling graduates to progress into research, teaching, and doctoral-level specialisation, ensuring continuity within the discipline.

A Programme Shaping Regional Practice

The reputation of Makerere University’s Bachelor of Environmental Health Science programme is also increasingly influencing regional institutions. During a strategic benchmarking visit to MakSPH on July 30, 2025, Dr. Ratib Dricile, Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences at Muni University, described the School of Public Health as a reference point for universities seeking to strengthen environmental health training in the region.

The main reason the delegation visited Makerere University School of Public Health was that Muni University remains a young and growing institution located in north-western Uganda along the borders with the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan, where porous borders contribute to frequent cross-border diseases, many of which are preventable through strong environmental health approaches, Dr. Dricile explained.

“Makerere University, with over 100 years of institutional experience and 25 years running the Environmental Health programme, was the right place for us to benchmark, particularly in curriculum design, course content, programme structure, and implementation,” he said. “We were impressed by the work being implemented and gained more than we initially expected. By integrating these experiences, we believe the Muni University curriculum can become even stronger. The collaboration will allow us to adopt innovations built on Makerere’s long experience, and we believe that working together with Makerere University will strengthen Muni University institutionally and contribute positively to our university’s growth and ranking.”

It is within this institutional tradition, built over decades of training environmental health professionals across Uganda and the region, that Philliph Acaye’s achievement takes meaning. For him, graduating top of the class remains grounded in practical purpose rather than prestige. He views a first-class degree as an opportunity rather than an endpoint. Recalling guidance from his lecturers, he said strong academic results can open doors but must be followed by demonstrated competence. “A first class helps you get shortlisted,” he said. “After that, you must prove yourself.”

His immediate plans reflect that perspective. He is currently pursuing additional training in Health Services Management at Gulu College of Health Sciences while preparing for postgraduate study in either public health or environmental and occupational health. At the same time, he continues supporting pupils in his community and plans to mobilise resources to provide sanitary pads for girls at his former primary school, an initiative he believes will help reduce school dropout rates in rural areas.

Acaye’s journey, from disrupted schooling in an IDP camp to graduating top of MakSPH’s BEHS programme for the 2022 cohort, reflects the deeper purpose of public health education. As MakSPH presents its newest cohort for graduation this week, his story demonstrates how the programme turns lived experience into professional capacity, strengthening communities and health systems across Uganda and the region, one graduate at a time.

Trending

-

Humanities & Social Sciences1 week ago

Humanities & Social Sciences1 week agoMeet Najjuka Whitney, The Girl Who Missed Law and Found Her Voice

-

General1 week ago

General1 week ago76th Graduation Highlights

-

Health2 weeks ago

Health2 weeks agoUganda has until 2030 to end Open Defecation as Ntaro’s PhD Examines Kabale’s Progress

-

Agriculture & Environment2 weeks ago

Agriculture & Environment2 weeks agoUganda Martyrs Namugongo Students Turn Organic Waste into Soap in an Innovative School Project on Sustainable Waste Management

-

General2 weeks ago

General2 weeks agoMastercard Foundation Scholars embrace and honour their rich cultural diversity