General

The Second Martin Luther Nsibirwa Annual Public Lecture

Published

2 years agoon

By

Mak Editor

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY LECTURE SERIES

The 2nd Annual Nsibirwa Public Lecture

Situating the Role and Relevancy of Cultural Institutions in Modern Uganda[1]

_________________________

The guest of honor, the Vice Chancellor of Makerere University, Officials of the Government of Uganda and the kingdom of Buganda, the family of the late Martin Luther Nsibirwa, distinguished guests, Ladies and Gentlemen.

I thank you all for the warm welcome and I particularly thank the Vice Chancellor, Professor Barnabas Nawangwe for inviting me to speak at the second annual Martin Luther Nsibirwa Lecture. I want to acknowledge his leadership in marking and celebrating 100 years of Makerere University. Many congratulations.

Today, we gather—not only to pay tribute to a remarkable man who played a pivotal role in the history of Buganda, Uganda and indeed the African continent — but to continue, in the celebrations of the centenary of Makerere University. It is a double celebration of knowledge, history, and progress and an opportunity to explore the dynamic role and relevance of cultural or traditional institutions in modern Uganda.

I cannot think of a more fitting occasion to commemorate these significant milestones. Because, even as we reflect on the legacy of Martin Luther Nsibirwa and the journey of Makerere University, we do not just revisit the issues that shaped our past but reflect on current ones so we may imagine a future of peace, prosperity, and progress for our country. At this moment, we are reminded of the power of education, vision, and resilience — values championed by Nsibirwa, and Makerere.

I am therefore deeply honored for the privilege accorded to me by the University to deliver this lecture. Makerere University, standing tall at a century of existence, has been the cradle of knowledge, a beacon of progress, and a source of pride for Uganda and Africa.

Makerere has shaped minds, fostered creativity, and ignited flames of change that continue to burn brightly today. Makerere’s journey has not been without hurdles, but each hurdle was an opportunity for growth and introspection, a testament to resilience of our people, the tenacity of our scholars and the dedication of University leaders, past and present. I salute the service of the late Frank Kalimuzo, Sentenza Kajubi, Asavia Wandera, George Kirya, John Sebuwuufu and others that have led this great University.

As a product of Makerere University, I was able to join and thrive at the University of Cambridgein the UK. While there I was mostly asked about Idi Amin Dada and Makerere University. I know many Makererenians that that have left a mark in the world including: Prof. Opiyo-Oloya at the University of Toronto, Canada, Professors Oloka-Onyango and Sylvia Tamale at the University of Harvard, Prof. Kanyeihamba and John Jean Barya at the University of Warwick UK., Prof. Dan Wadada Nabudere at the University of Dar es Salaam; Benjamin Mkapa ex-president of Tanzania; Prof Edward Khiddu Makubuya at Yale and Prof Mamdani at Colombia and numerous others anti Omuto Gyamanyi….

I extend my gratitude to the Nsibirwa family for preserving Nsibirwa’s legacy, and commend individuals like Hon. Rhoda Kalema, Owek. Robert Waggwa Nsibirwa, Hon. Maria Kiwanuka, Dr. Gladys Zikusooka, Dr. William Kalema, Susan Nsibirwa, and other Nsibirwas for their outstanding contribution to Uganda and the world.

Unlike the professors I mention above, Martin Luuther Nsibirwa, had no formal education. He grew up under the patronage of Sir Apollo Kaggwa and taught himself how to read and write. He served the kingdom of Buganda for an uninterrupted period of 41 years. He started as a land clerk, became a Gombolola chief and later as a Ssaza Chief (Mugerere and Mukwenda) he was appointed as the Omuwanika in 1935 and later as Katikkiro by Sir Daudi Chwa in 1936, and by Sir Edward Muteesa in 1945.

I joined Makerere University in 1987 and was admitted to Northcote Hall. I suspect there are some Northcotters (noise makers?) in this room! This hall of residence was named after Sir Geoffry Alexander Stafford Northcote a British colonial Administrator.[2] I was at once immersed in the culture of the Northcote Spirit – a spirit that invariably involved singing, drumming and a culture of militancy and defiance under what was known as the Northcote Military Supreme Command Council. I rose in the Northcote military ranks to become a speaker for the Northcote Colloquium. But even at the height of my Northcote officialdom, I never knew, or questioned who Northcote was or what he represented. It is only recently, in my campaign to end the celebration of colonial subjugators and to remove street names like Fredrick Lugard, Henry Colville and Trevor Ternan that I discovered the true history of Northcote.

Northcote was posted to Nyanza Province which was then part of Uganda. In early 1905, he was part of a punitive expedition to Kisii land in South Nyanza. The expedition carried out a month-long orgy of violence as punishment for raids the Kisii had carried out. In 1907, Northcote was deployed as the District Commissioner of Kisii. The Kisii, who nicknamed him Nyarigoti, considered him their mortal enemy. On 18 January 1908, in the middle of a punitive expedition he was leading, Northcote was attacked with a spear and injured by a warrior called Otenyo. When Otenyo was caught, he was tried in public, dragged by a horse and executed in public by a firing squad. He was then beheaded and his body shipped to London. Northcote’s expedition was responsible for the death of hundreds of Kisii’s. On his recent visit to Kenya, King Charles III stated that Britain’s “wrongdoings of the past are a cause of the greatest sorrow and the deepest regret.” He said these actions were “abhorrent and unjustifiable acts of violence committed against Kenyans”.

It is therefore curious that the leadership of Makerere University at the time found it fitting to name a major hall of residence after Sir Geoffry Alexander Stafford Northcote. This brings to light the question of why we continue to honor and celebrate such figures in our universities and public spaces across the country.

I applaud the decision to change the halls name from Northcote to Nsibirwa and Makerere’s leadership in recognizing heroes like Okot p’tek, Yusuf Lule, Kwame Nkrumah, and Patrice Lumumba. I hope they will find some space for other notable alumni like Ngugi wa Thiong’o one of Africa’s leading writers and the author of “Decolonising the Mind”.

As a part of decolonising the University, I consider that an individual that ought to be celebrated is the late Joan Namazzi Kagezi an alumni of this University— assassinated in line of duty. Joan, like my wife here, Omumbejja Anne Nakayenga Juuko a granddaughter of Ssekabaka Basamula Ekkere Mwanga, was a beautiful, brilliant, and a brave woman. As a heroine of our generation, she deserves our admiration and honour.

Vice Chancellor, embracing decolonisation in the teaching and learning at Makerere and beyond, is essential to debunk Eurocentric narratives of our history and society, and to provide a more accurate representation of our heritage.

Nsibirwa, along with other Baganda leaders such as Apollo Kaggwa, Ham Mukasa, Wamala, Semei Kakungulu, Gabriel Kintu, Matayo Mugwanya, Micheal Kintu , Eridad M. K Mulira and Ignatius Musaazi led Buganda at a turbulent time, marked by the struggle against British imperialism in Uganda. It was a time of profound contradictions between traditional leadership and colonial rule; traditional religion and Christianity; and African nationalism and imperial domination. Difficult choices had to be made either to preserve a traditional order or embrace a foreign and modern one. The clashes that arose in this context were numerous and often resulted in protests and loss of lives.

For Nsibirwa, these contradictions proved costly. His views as a devout Christian and a progressive leader, on matters like the remarriage of Namasole Drussila Namaganda (Kabaka Muteesa II’s mother) to Simon Peter Kigozi cost him his Katikkiroship. This is because the remarriage of a Namasole was a taboo in Buganda. Nsibirwa was replaced by Katikkiro Wamala an ultra-traditionalist and anticolonialist. He is said to have been behind 1945 protests in Buganda. Once Wamala’s group was ousted from power and summarily deported, the colonial government weighed on Kabaka Muteesa II to reinstate Nsibirwa as Katikkiro. Once back in power, Nsibirwa immediately embarked on implementing the not so popular land reforms in Buganda. In this effort he championed the grant of the land at Makerere for the construction of a Technical College. For this and other reasons he was assassinated at Namirembe Cathedral on 5 September 1945.

The date of 5 September is ominous to the Nsibirwa family because on that same date it lost Stella Nansikombi Mukasa to cancer. Stella, an alumnus of Makerere University, was a leading light in the advancement of women’s rights in the world. A conference hall has been named after her at the headquarters of the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) in Washington DC.

The fate suffered by Nsibirwa at once illustrated the challenges faced by traditional leaders in serving the interests of their communities while accommodating the interests of the colonial power. The interest of the two entities were dichotomic and opposed to each other. While the objective of colonialism was to supplant traditional authority and replace it with a political and economic structure that served its exploitative interests; the aspiration of African traditional entities was to end colonial domination and to reinstate traditional sovereignty. In this contest and given the power relations between the two the imperialism prevailed leaving traditional entities emasculated.

This is seen in the draconian deposition and deportation of Kabaka Mwanga, Omukama Kabalega and Muteesa II who were resistant to the colonial domination. The weakening of traditional entities continued in various forms right up to the time of Independence. And although the kingdom of Buganda tried to break free in 1960, its attempts were thwarted resulting in its incorporation into the country what we know as Uganda today. But the sacrifices and resilience of leaders like Nsibirwa led to Uganda’s independence in 1962.

The fate of traditional leaders and Institutions did not improve after Uganda got independence. In fact, traditional institutions were abolished in 1966. This was because after independence, Uganda’s new political elite faced the complex challenge of reconciling traditional governance with western democratic ideals. The clash between traditional governance structures and Western-style democracy presented a dilemma. The new leaders faced a conundrum in managing traditional leaders with ancient institutions and traditions in a new country.

Striking a balance was no easy task especially because there was mistrust between the new politicians and traditional leaders. This mistrust gave birth to the notion that African tradition and governance were the antithesis of democracy and thus an obstacle to development and modernity. Like the colonialists that preceded them, frowned upon traditional institutions¾relegating them as outdated, parochial, and tribal. They entrenched autocracy, centralised state power, and relied on legal and political systems inherited from the colonial era upholding Western ideals over indigenous ones.

However, the diminution or abolishment of traditional leadership in Africa did not lead to peace and progress – instead many African countries, Uganda included, ended up in failure of Western models of democracy leading to political crises, military coups and in some instances, state failure.

Today, 60 years after independence, Africa grapples with a crisis of governance, corruption, and underdevelopment. It is in this context that we see a resurgence of traditionalism driven by a renewed interest in cultural heritage and the wisdom and knowledge of our ancestors. This trend offers a sense of identity and stability in an ever-changing world. It is a testament to the enduring power of Africa’s cultural heritage. This trend raises critical questions:

- Can kingdoms or traditional institutions coexist with within a modern postcolonial state?

- Do they provide solutions for service delivery, poverty eradication, conflict resolution and governance? [3]

- Does their resurgence challenge modern states and inherited notions of democracy?

- Can a blend of modern and traditional systems foster political stability and development?

- If so, are there justifiable constitutional limitations on these institutions?

To answer these questions, we must consider the significance of the restoration of traditional rule in Uganda in the last 30 years. What do we see?

- A proliferation of traditional institutions beyond the Buganda, Busoga, Ankole, Tooro, and Bunyoro kingdoms that were recognised at independence.[4] As of 2023, excepting the ambiguous statuses of the Omugabe of Ankole,[5] the Banyole Cultural Institution,[6] and the Bunyala Cultural Institution,[7] fourteen traditional institutions or leaders have been officially recognised.[8] Fifteen others have applied for recognition.[9] If these were to be admitted the total number of traditional institutions in Uganda would be twenty-nine, almost half of Uganda’s sixty-five indigenous communities.[10] But the growth in number of traditional institutions has not meant that they have become more influential or powerful actors in the political economy of Uganda. Most traditional institutions are marginalised, fragmented, and dependent on the state for survival.

- Some face internal conflicts and crisis of legitimacy of its leaders.

- There exists discordance with the central government on several issues including the non-return of expropriated assets, on land tenure, and the creation or support of sub traditional entities such as the Burulri, Bunyalas and Kooki in Buganda. Discordance on these policies has sometimes resulted in violence as was seen in the 2009 protests in Buganda and killings in the Obusinga bwa Rwenzururu and the arrest and detention of its king, Omusinga Mumbere, in 2016. These tensions showcase the delicate nature of power sharing in modern Uganda and a need for reconciliation and dialogue.

- Evidence of collaboration in noncontentious fields —education, poverty alleviation, health, environment, and culture. Covid, Fistula, Vaccinations, HIV and Aids etc.

- Evidence of growing popularity of the Kabakaship in Buganda. The Kabaka and Buganda kingdom continue to be popular and to exercise considerable soft power. The Kabaka is revered as a custodian of culture and a source of guidance and inspiration for his people. This is evidenced by the high numbers that turn out at cultural and other kingdom ceremonies. Additionally, the involuntary financial support given to the kingdom suggests that it enjoys both legitimacy and credibility. Buganda kingdom serves as a significant pressure group for politicians despite its constitutional limitations as a cultural entity.

- The support enjoyed by Buganda kingdom today at once highlights nagging political questions in Uganda and problematises its governance and constitutional model. Can the kingdom’s popularity be harnessed for political stability and socioeconomic development for all? The kingdom argues that through a federal system of government it can make a more meaningful contribution to its subjects as well as to the country.

From the above, traditional institutions continue to play a vital role culturally, economically, and politically. They bring stability, cultural preservation, and a sense of unity. They deserve attention and recognition for this role. But at the same time manty face limitations in adapting to the complex challenges of the modern world.

In the case of Buganda, two issues stand out for discussion namely, the Federal Question and the Land Question. These remain thorny unresolved issues in Buganda and Uganda’s relationship. Why ?

The Land Question:

In the context of increased pressures on land due to population and economic growth, Uganda is witnessing unprecedented levels of land grabbing[11] and the violent eviction of people from land across the country. Yet the state’s responses to stem the evictions and to reform land laws have not always provided effective solutions to the problem but have instead aggravated it.

- A clash on laws and policies on land tenure between the central government and the kingdom of Buganda. Specifically, the government’s policy intentions to create radicle title of land; to abolish mailo[12] land tenure and to compulsorily acquire land without prompt and due compensation.

- Competing interests of land rights between the landlords and lawful (kibanja holders) or bona fide occupants of land. The fixing of land rent at nominal rates regardless of the location (rural or urban), user (commercial or residential), and size of the land. This is related to the scourge of land grabbing and forceful evictions of occupants of land, and has contributed to the escalation of disputes involving Kabaka land.[13]

- Refusal and or delay in the return and/or compensation of expropriated lands. The government’s ambivalence to account for the 9,000 sq. miles[14] and other confiscated lands to the kingdom of Buganda and its refusal to hand over all the public land in Buganda to the kingdom has been a source of conflict. This problem has been exacerbated by the conversion of public land into freehold land tenure.

- Weak mechanisms for the resolution of land disputes. This is despite the many bodies that have been created to address land disputes under the police, judiciary, President’s Office, the Land Fund and the Ministry of Lands.

- The disputed boundaries and ownership of Kampala capital city.

- The disposition and privatisation of clan lands (Obutaka) under the 1900 Agreement.

The Federal Question:

The quest for autonomy and federal rule in Buganda has been fraught with challenges, symbolising the difficulties in balancing traditional authority with central governance.From its restoration to the present day, the kingdom of Buganda has resisted a unitary arrangement demanding instead federal rule. Why? Its reasons are set out in various memoranda to the government,[15] but may be summarised in its interest in power sharing and self-determination, the accommodation and respect for Uganda’s ethnic diversity, the preservation of cultural heritage, the protection of its natural resources¾especially land¾and the promotion of its indigenous institutions and governance systems that served it well in the past. The kingdom points to the conflicts and failures of unitarist governance founded on a colonial legacy and advocates for a constitutional order that recognises and respects traditional authority. It believes that federalism leads to better representation and local accountability, and that it ensures the equitable distribution of resources and reduces disparities in development. In a nutshell, the federal question is a governance question—relating to a suitable system of government that respects the will and aspirations of the people.

In an undemocratic way, the government disregarded the overwhelming support for the adoption of federal rule and imposed a unitary system in the 1995 Constitution. It argued that the objectives of federalism could be attained through decentralisation.[16] A disappointed Buganda disagreed with this view, arguing that decentralisation was a ploy to defeat or delay its demands. Today, the federal question in Uganda remains in a stalemate. Neither the central government nor the kingdom of Buganda has changed its position, and there is little likelihood that this will change soon. There is a need to find solutions to this problem. Africa is replete with examples of successful integration of traditional institutions into modern governance structures, striking a balance that respects tradition while embracing modern forms of governance. In its search for solutions, Uganda needs to study and take lessons from experiments of federalism and devolution in Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, and Sudan.

A national dialogue? Besides the federal question, Uganda has many unresolved issues, such as land tenure and the militarisation of politics, that require nation-wide consultations and consensus outside the present political and constitutional structures. For this reason, citing the lack of constitutionalism, intolerance of political dissent, increased poverty levels, poor performance of the social services, rampant corruption, and contested elections marred by violence in Uganda, religious leaders and elders have called for a national dialogue to build a consensus on the achievements, failures, and future of an independent Uganda.The goal of the dialogue is to “agree on a new national consensus to consolidate peace, democracy, and inclusive development to achieve equal opportunity for all.”[17] In September 2018, President Museveni launched the National Dialogue, but little progress has been made on this matter since then.[18] While the reasons for the stagnation of dialogue are unclear, the need for it remains undeniable.

30 years later – Traditional institutions still at sea? The case of the Buganda kingdom exemplifies how the authority and legitimacy of traditional leadership warrant a reevaluation of the governance and constitutional models adopted in Uganda and in other African countries. By recognising and incorporating traditional institutions into the fabric of governance, justice, and social cohesion efforts, some persistent and complex issues, such as the Buganda Question, can be addressed in the postcolonial era. It is important to acknowledge the internal weaknesses and lack of homogeneity within these institutions, matters which undeniably present challenges as to how they may be viably integrated into modern governance systems.

Conclusion:

The challenges of governance and underdevelopment in Africa are vast, but traditional institutions and leaders have a significant role to play. The future of Africa is promising provided we adapt it to meet the evolving needs of our societies while preserving our identity and values.

By addressing limitations of traditional entities, shedding the legacy of colonialism, and embracing a dual approach that combines both traditional institutions and modern systems, Africa can chart a path towards inclusive development—one rooted in its rich cultural heritage and diverse traditional practices.

Leaders like Nsibirwa and institutions like Makerere University inspire us to tackle the challenges of development and governance with education, innovation, and a commitment to our people’s well-being. We must preserve these legacies and carry the torch of knowledge forward. It is up to us to shape the future and illuminate the path for generations to come.

Hillary R. Clinton, former US Secretary of State, and first lady, in a speech delivered in here at Makerere’s Freedom Square in 1998, stated that the struggle to protect human rights (and overcoming the challenges we face as a country) depends upon the millions of actions that are taken every day by ordinary people like us. She said that “those of us who have the power to speak, and all of you here who are affiliated with this great university, by virture of you being here and attaining this education, not only have the power to speak, but the obligation to do so.”

As our country’s history shows, there is much we can speak against in Uganda. There is so much that needs to be done. We have a duty to do so.Like the Nsibirwa’s before us, we must stand up, we must speak up, and together, we must build our country and our University for a brighter and better future!

Back in the day, at this point I would say, “Northcote OYEE!!” but I believe it is more fitting to say “Nsibirwa OYEE!! “

Thank you very much and may God Bless you all.

Apollo N. Makubuya

Kampala, 9 November 2023.

[1] Apollo N. Makubuya , The Nsibirwa Annual Public Lecture, Makerere University, 9November 2023.

[3] The governance crisis is multifaceted and affects various African countries differently, but essentially entails the failure of democratic rule, autocracy, military rule, and corruption leading to poverty and underdevelopment.

[4] Article 89 of the 1962 Constitution provided for the creation of constitutional heads for districts. These could be chiefs.

[5] The non-recognition of the kingdom of Ankole is contested, as it contradicts the restoration policy and has contributed to further division within the Bahima and Bairu groups in Ankole, leading to the loss of the kingdoms prominence. See John-Jean Barya (1998), “Democracy and the Issue of Culture in Uganda: Reflections on the (Non)Restoration of the Ankole Monarchy,” East African Journal of Peace and Human Rights Vol. 4, Issue 1: pp. 1–14.

[6] See “Why Banyole Have Failed to Have a King for 14 Years,” Daily Monitor, 11 May 2023.

[7] See “Kabaka Restates Case for Federo,” The Monitor, 17 December 2009.

[8] Namely, the Kabaka of Buganda, the Omukama of Tooro, the Omukama of Bunyoro, the Kyabazinga of Busoga, the Omusinga of Rwenzururu, the Ker of Alur, the Ker Kwaro of Acholi, the Te Kwaro of Lango Cultural Foundation, the Tieng Adhola of Japadhola, the Emorimor Papa of Iteso Cultural Union, the Isabaruli of Buruli, the Kamuswaga of Kooki, Inzu ya Masaba of Bugisu, and Obudhingiya bwa Bamba.

[9] Namely, the Kitisya of Bugwere/Nagwere Kimadu, Bagwe of Tororo, Babukusu of Bududa, Banyala, Basongora, Jonam Koc Chiefdom (Wedelai Koc), Dikiri pa Rwodi Mi Cak Jonam (Ker Kwaro), Banyabindi, Lugbara, Ker Kwonga of Panyimur, Kebu- Rirangi-Zombo, Ambala Aringa of Yumbe, Ntusi/Bigo bya Mugenyi, Kusaalya bya Kobhwamba and Obwenengo bwa Bugwe.

[10] See 3rd Schedule of the Constitution of Uganda.

[11] Land grabbing takes the form of powerful individuals with political influence and/or money or the military taking advantage of peasant populations to purchase their land at giveaway prices and/or evict them from land.

[12] The word ‘mailo’ is the Ugandan expression of the English word “mile.’ Mailo land tenure has characteristics similar to English freehold land tenure.

[13] At the time of publication of this paper the Kabaka and/or Buganda Land Board was involved in more than fifty court cases on competing claims on ownership, trespass, criminal violence, and lease rights.

[14] See Ministerial Statement to Parliament: 9000 Square Miles of Land in Buganda by the Hon. (Dr) Edward Khiddu-Makubuya, Attorney General/Minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs, dated 5 March 2008.

[15] In August 1991, Ssaabataka Supreme Council met with Museveni in Entebbe to discuss the restoration of the monarch and the return of Buganda’s expropriated assets (Ebyaffe). It was agreed that Buganda should submit detailed proposals on these issues to the UCC. On 30 August 1991, the Council, led by Prof. Apolo Nsibambi, submitted Buganda’s proposals on the restoration of traditional leaders in areas that wanted them and a federal form of government amongst others.

[16] See Odoki J. Benjamin (2005), The Search for National Consensus: The Making of the 1995 Uganda Constitution (Kampala, Uganda: Fountain Publishers), p. 204.

[17] See The Uganda National Dialogue Process Framework Paper,December 2017.

[18] See “Museveni Launches National Dialogue, Lists Four Issues,” Daily Monitor, 18 December 2018.

You may like

-

Over 9,200 to graduate at Makerere University’s 76th Graduation

-

Meet Najjuka Whitney, The Girl Who Missed Law and Found Her Voice

-

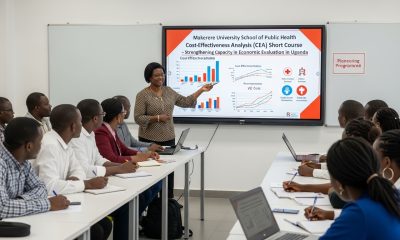

Makerere University School of Public Health Graduates First Cohort of Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Short Course

-

Climate variability found to shape malaria trends in Yumbe District

-

Mak hosts First African Symposium on Natural Capital Accounting and Climate-Sensitive Macroeconomic Modelling

-

Uganda Martyrs Namugongo Students Turn Organic Waste into Soap in an Innovative School Project on Sustainable Waste Management

General

Over 9,200 to graduate at Makerere University’s 76th Graduation

Published

4 hours agoon

February 24, 2026

Pomp and colour defined the opening day of the Makerere University’s 76th Graduation Ceremony as thousands gathered to celebrate academic excellence and new beginnings.

The historic ceremony has brought together scholars, families, friends and industry partners in a vibrant celebration of achievement and possibility. Throughout the four-day event, the University will confer degrees and award diplomas to 9,295 graduands in recognition of their dedication and hard work.

Among the graduates, 213 will receive Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degrees, 2,503 will graduate with Master’s degrees, and 6,343 will earn Bachelor’s degrees. In addition, 206 students will graduate with postgraduate diplomas, while 30 will be awarded undergraduate diplomas.

Of the total number of graduands, 4,262 are female and 5,033 are male. According to Vice Chancellor, this marks the first time in 15 years that male graduands have outnumbered their female counterparts.

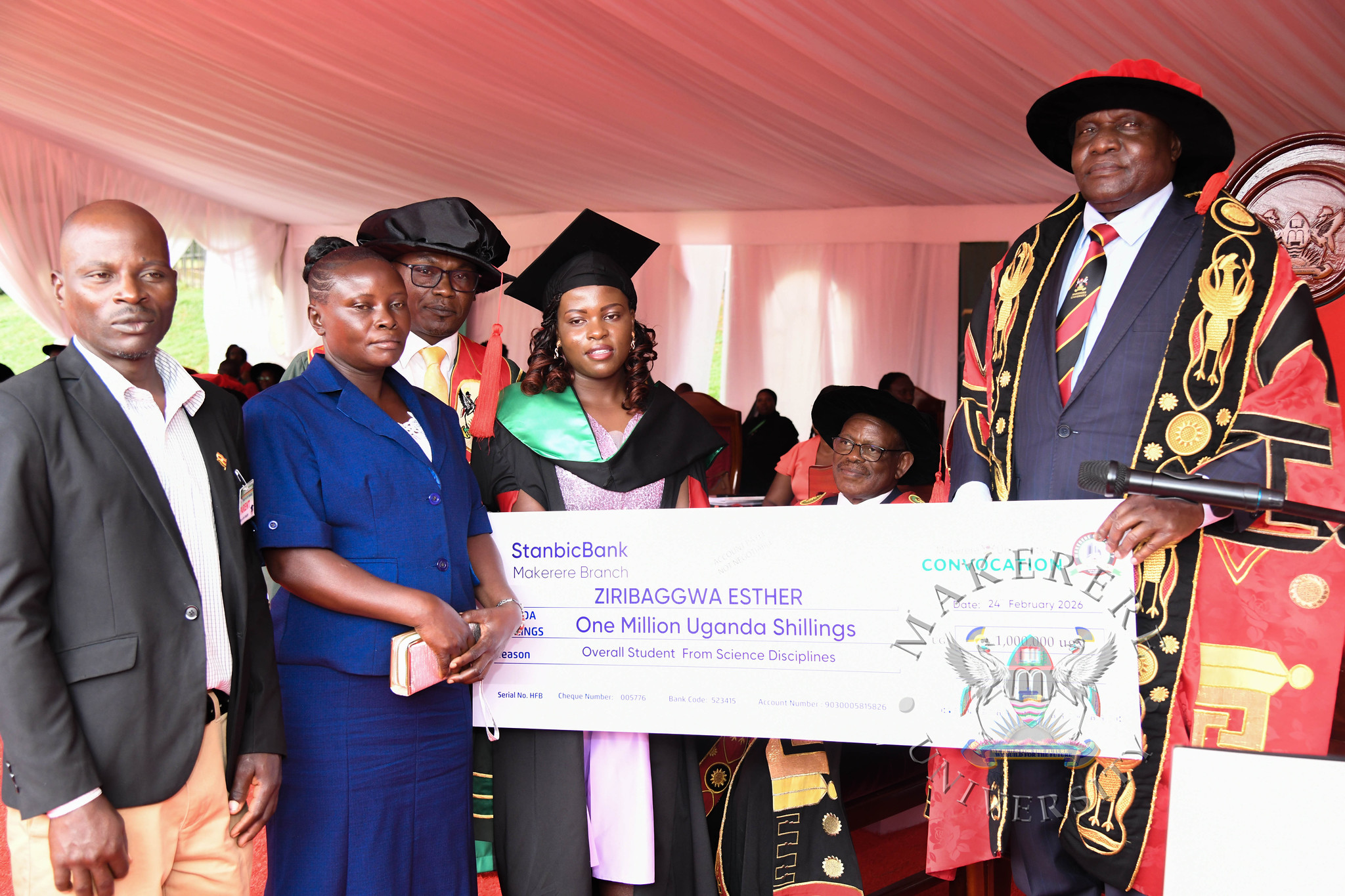

The best overall graduand in the Sciences, Esther Ziribaggwa, graduated on the opening day with the Bachelor of Agricultural and Rural Innovation and an impressive Cumulative Grade Point Average (CGPA) of 4.77.

The ceremony marks a proud moment for Makerere University as it continues to nurture top-tier professionals across diverse fields.

While presiding over the graduation, the State Minister for Primary Education, Hon. Dr. Joyce Moriku Kaducu, on behalf of the First Lady and Minister of Education and Sports, Hon. Janet Kataaha Museveni, pointed out that Makerere University is a model institution, where leaders are nurtured, scholars are sharpened, and where dreams have been given direction.

In her address, Hon. Museveni, highlighted Government’s deliberate investment in research, innovation, and infrastructure to strengthen higher education in Uganda.

“The establishment of the Makerere University Research and Innovation Fund (RIF), supports high-impact research and innovation that directly contributes to national priorities and development. Through this initiative, thousands of researchers and innovators have pursued practical, scalable solutions that are transforming communities and key sectors across Uganda,” Mrs Museveni, said.

The Minister also noted that Parliament’s approved a USD 162 million concessional loan to upgrade science, technology, and innovation infrastructure at Makerere University. The funding will facilitate the construction of modern laboratories, smart classrooms, and state-of-the-art facilities for Engineering and Health Sciences, investments expected to position the University firmly within the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

“Government has embarked on the construction of a National Stadium at Makerere University and other institutions of higher learning across the country. This will promote physical education, strengthen talent identification, and boost investment in the sports sector,”

Turning to the graduands, the Minister encouraged them to see themselves not merely as job seekers, but as job creators and solution-makers.

Uganda and Africa need innovators who will modernize agriculture; engineers who will build quality infrastructure; healthcare professionals who will strengthen health systems; and educators who will inspire the next generation,” the Honourable Minister said.

She reminded graduates that they are entering a rapidly changing world shaped by Artificial Intelligence, climate change, and shifting global markets. To thrive, she advised them to remain adaptable, creative, and committed to lifelong learning.

She also encouraged graduates interested in entrepreneurship to tap into the Government’s Parish Development Model, which provides community-based financing and production support.

Quoting Proverbs 3:5–6, the Minister urged the graduates to trust in God as they embark on their next chapter.

She extended special appreciation to the Mastercard Foundation for its 13-year partnership with Makerere University in expanding access to education and empowering young people in Uganda and beyond.

In his speech, the Chancellor of Makerere University, Dr Crispus Kiyonga, urged graduands to harness research, innovation and technology to drive Uganda’s transformation.

“This is a milestone in your lives. You have invested time, discipline and hard work to attain these qualifications. It is important that you derive value from this achievement, not only for yourselves, but for your families and for society.” Dr Kiyonga, said.

Dr. Kiyonga expressed gratitude to the Government of Uganda for its continued financial support to the University, particularly the funding allocated under MakRIF, which he described as critical in strengthening the institution’s research capacity.

“Research plays a very vital role in the development of any community. Makerere as the oldest University in the country is doing a significant amount of research, However, more work is required to mobilize additional resources to further strengthen research at the University.” Dr Kiyonga, noted.

Acknowledging the challenges of a competitive job market, Dr. Kiyonga encouraged graduates to think beyond traditional employment pathways.

“It is true that the job market may not absorb all of you immediately. But the knowledge you have acquired is empowering. You can create work for yourselves, individually or in teams.” Dr Kiyonga, said.

He advised the graduands to embrace discipline, integrity and adaptability in the workplace, and to take advantage of technology and digital platforms to innovate and respond to societal challenges.

“Every development challenge presents an opportunity. Believe that you can apply your knowledge to create solutions with impact.” He said.

Addressing the congregation, the Vice Chancellor, Prof Barnabas Nawangwe, congratulated the graduands, particularly staff and societal leaders on their respective achievements.

“I congratulate all our graduands upon reaching this milestone. In a special way I congratulate the members of staff, Ministers, and Members of Parliament that are graduating today as well as children and spouses of members of staff,” Prof Nawangwe, said.

In his speech, Prof Nawangwe, recognized outstanding PhD students, particularly members of staff. who completed their PhDs in record time without even taking leave from their duties.

He called upon graduates not to despise humble beginnings but rather reflect on the immense opportunities around them and rise to the occasion as entrepreneurs.

“You are all graduating with disciplines that are needed by society. We have equipped you with the knowledge and skills that will make you employable or create your own businesses and employ others. Do not despair if you cannot find employment. Instead, reflect on the immense opportunities around you and rise to the occasion as an entrepreneur,” Prof Nawangwe, said.

Prof Nawangwe called upon the graduands of PhDs to use their degrees to transform the African continent.

“As you leave the gates of Makerere I urge you to put to good use the knowledge you have received from one of the best universities in the World to improve yourselves, your families, your communities, your Country and humanity. Let people see you and know that you are a Makerere alumnus because of the way you carry yourself in society with dignity and integrity. Put your trust in God and honour your parents and opportunities will be opened for you,” Prof Nawangwe, said.

Delivering a key note address, Prof. Nicholas Ozor, the Executive Director of the African Technology Policy Studies Network Nairobi, Kenya ((ATPS). Reminded the graduates that a degree is not a finish line but the beginning of accountability. “The world is a complex, fast changing and deeply unequal. Degrees make you responsible for others not better than them,” Prof Ozor, said.

The 76th Graduation Ceremony of Makerere University will be held from Tuesday 24th to Friday 27th February, 2026. A total of 213 PhDs (87 female, 126 male), 2,503 Masters (1,087 female, 1,416 male), 206 Postgraduate Diplomas (80 female, 126 male), 6,343 Undergraduate Degrees (2,999 female, 3,344 male), and 30 Undergraduate Diplomas (9 female, 21 male) will be graduating from all the Colleges.

Ms. Sarah Aloyo and Ms. Nakato Dorothy both students of the Bachelor of Procurement and Supply Chain Management emerged as the best in the Humanities and Best Overall students with a CGPA of 4.93. Mr. Ssewalu Abdul, a Bachelor of Leisure and Hospitality Management student emerged second best in the Humanities with a CGPA 4.90. Ms. Esther Ziribaggwa emerged as the best student in the Sciences with a CGPA of 4.77 in the Bachelor of Agricultural and Rural Innovation, while Mr. Simon Mungudit emerged second best in the Sciences with a CGPA of 4.76 in the Bachelor of Science in Petroleum Geoscience and Production.

Commencement Speakers

- Day 1 – Prof. Nicholas Ozor, the Executive Director of the African Technology Policy Studies Network, Nairobi, Kenya

- Day 2 – Prof. Dr. Maggie Kigozi, Chairperson Makerere University Endowment Fund Board

- Day 3 – Dr. Patricia Adongo Ojangole, Managing Director, Uganda Development Bank Limited

- Day 4 – Ms. Reeta Roy, Former President & Chief Executive Officer, Mastercard Foundation

The 76th Graduation Ceremony will be held at the Freedom Square following the schedule below:

Tuesday, 24th February, 2026

College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES)

College of Computing and Information Sciences (CoCIS)

College of Education and External Studies (CEES)

School of Law (SoL)

Livestream Link for Day 1: https://youtube.com/live/wVGPA0FJ9pU

Wednesday, 25th February, 2026

College of Health Sciences (CHS)

College of Natural Sciences (CoNAS)

College of Veterinary Medicine, Animal Resources and Bio-security (CoVAB)

School of Public Health (SPH)

Thursday, 26th February, 2026

Makerere University Business School (MUBS)

College of Business and Management Sciences (CoBAMS)

Friday, 27th February, 2026

College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology (CEDAT)

College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHUSS)

Institute of Gender and Development Studies (IGDS)

Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR)

General

Mak Selected to Host Alliance for African Partnership Africa Office

Published

1 day agoon

February 23, 2026

Makerere University has been selected to host the Africa Office of the Alliance for African Partnership (AAP). The significant milestone that underscores Makerere’s role in fostering research, innovation, and global collaborations across the continent was announced at a meeting of the University’s Central Management with an AAP delegation on 23rd February 2026.

Makerere’s selection was based on the University’s robust commitment, alignment with the AAP’s Strategic Plan, and proven ability to manage consortium activities. The AAP, which was initiated by Michigan State University (MSU) in collaboration with Ten African Universities and agricultural policy research networks in 2016, targets critical challenges in education, youth empowerment, health and nutrition, agri-food systems, science and technology, water, energy, environment, and culture and society.

Addressing the delegation consisting of AAP Co-Directors from MSU, Dr. Jose Jackson-Malete and Dr. Amy Jamison, accompanied by newly-appointed Director of the AAP Africa Office, Dr. Racheal Ddungu Mugabi and Ms. Clare Cheromoi, the Vice Chancellor, Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe who appreciated the choice of Makerere to host the Africa Office said:

“One of the greatest challenges facing African universities is PhD training, particularly supervisory capacity. Through partnerships such as the Alliance for African Partnership we can leverage international expertise to strengthen supervision—whether through training supervisors or through joint supervision arrangements.”

Prof. Nawangwe equally applauded joint initiatives such as the Grant Writing and Publication project, which gave rise to the establishment of a Writing Centre that he said can be used to build capacity in AAP member universities with Makerere as the hub. Officially launched on 21st March 2023, the project is living up to its expectation of becoming a springboard for strong postdoctoral collaborative research for both institutions and other US universities.

Dr. Titus Awokuse, Vice Provost and Dean for International Studies and Programs at Michigan State University (MSU) who attended virtually, reiterated that Makerere’s selection reflects its long-standing commitment to advancing African higher education, research excellence, and meaningful global collaboration.

Reflecting on the origins of the Alliance for African Partnerships (AAP), Dr. Awokuse explained that nearly a decade ago, MSU initiated a transformative conversation in Atlanta centered on the question: How should we partner differently? From this dialogue emerged AAP—an Africa-centered consortium that now brings together 12 institutions across Africa and the United States.

He emphasized that AAP is grounded in equity, mutual benefit, shared leadership, and deep respect for African priorities and expertise. Since its founding, MSU has served as convener and key supporter, working with member institutions to strengthen research collaboration, promote faculty and student engagement, and address shared development priorities.

Dr. Awokuse underscored that AAP’s success is the result of collective vision and commitment, not the efforts of a single institution. He paid tribute to Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources for hosting the Africa Office in its early years and acknowledged the foundational leadership of the inaugural Africa Office Director.

He described the launch of the Africa Office at Makerere University as a significant milestone that reinforces Africa-led leadership, strengthens regional collaboration, and enhances responsiveness to emerging opportunities. MSU, he affirmed, remains fully committed to AAP and to working closely with Makerere and all consortium partners to expand collaborative research, nurture the next generation of scholars, and advance Africa-led solutions to global challenges.

The newly-appointed AAP Africa Office Director, Dr. Racheal Ddungu Mugabi is a member of faculty in the Department of Development Studies, Institute of Gender and Development Studies. Her work on intersectional inequalities in Uganda and other Global South regions uniquely positions her to drive collaborative research and partnerships at the Africa Office.

Initially founded by ten African Universities and MSU, AAP now comprises eleven African members including; the African Network of Agricultural Policy Institutes (ANAPRI)-Zambia, Egerton University-Kenya, Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (LUANAR)-Malawi, Makerere University-Uganda, United States International University-Africa-Kenya, Universite Cheikh Anta Diop-Senegal, Universite Yambo Ouologuem de Bamako-Mali, University of Botswana-Botswana, University of Dar es Salaam-Tanzania, University of Nigeria, Nsukka-Nigeria, and the latest, University of Pretoria-South Africa.

These Universites collaborate under Focal Points to advance policy-relevant research and sustainable development. Makerere University’s Focal Point is Prof. Robert Wamala, Director of Research, Innovations and Partnerships (DRIP).

Addressing the University Management, Dr. Jackson-Malete outlined the African Futures Research Leadership Program, which nurtures early career scholars through mentorship and skill-building as one of AAP’s flagship programs. She noted that the Program that prioritizes female participants or men committed to promoting women in higher education has for the first time during its fifth cohort admitted the first male, Dr. Alfadaniels Mabingo from the Department of Performing Arts and Film, Makerere University.

The AAP Africa Office at Makerere will coordinate activities, boost research collaboration, mobilize resources, and enhance global engagements for socio-economic transformation. This aligns with Makerere‘s broader goals of leveraging international expertise to build resilient institutions.

View more photos from the event: https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjCLjoA

Trending

-

Humanities & Social Sciences2 days ago

Humanities & Social Sciences2 days agoMeet Najjuka Whitney, The Girl Who Missed Law and Found Her Voice

-

Health6 days ago

Health6 days agoUganda has until 2030 to end Open Defecation as Ntaro’s PhD Examines Kabale’s Progress

-

Agriculture & Environment5 days ago

Agriculture & Environment5 days agoUganda Martyrs Namugongo Students Turn Organic Waste into Soap in an Innovative School Project on Sustainable Waste Management

-

General6 days ago

General6 days agoMastercard Foundation Scholars embrace and honour their rich cultural diversity

-

Health2 weeks ago

Health2 weeks agoCall for Applications: Short Course in Molecular Diagnostics March 2026