Health

MakSPH, DJC Launch Short Course on Health Communication

Published

7 months agoon

By Okeya John and Primrose Nabankema

The intensive one-month course, running for the first time from June 5 to July 24, 2025, is jointly offered by Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH)’s Department of Community Health and Behavioural Sciences (CHBS) and the Department of Journalism and Communication (DJC) at the School of Languages, Literature, and Communication (SLLC), co-designed in 2024 with support from the Rockefeller Foundation through Amref Health Africa.

It seeks to equip healthcare providers at the community level, public health and environmental health practitioners, communication specialists, health educators, community development officers, social scientists, and policy makers, among others, with strategic communication skills to improve public health messaging, strengthen community engagement, and support evidence-based interventions, ultimately empowering participants to effectively engage communities and improve population health outcomes across Uganda and the region.

Launching the course, the heads of the Department of Journalism and Communication and the Department of Community Health and Behavioural Sciences noted that participants who complete the short course will gain practical tools to influence behaviour change, build trust, and deliver timely, accurate, and relevant health information to the communities they serve. The first cohort attracted more than 60 applicants, with 36 reporting for the opening in-person session on June 5, 2025, at MakSPH in Mulago. Between now and July, participants will undergo a hands-on, multidisciplinary learning experience within the Certificate in Health Communication and Community Engagement program, which combines theory and practice.

Among the participants in the first cohort of the certificate course, designed as a pilot for the anticipated Master of Health Promotion and Communication to be jointly offered by the two departments at Makerere University, is Ms. Maureen Kisaakye, a medical laboratory technologist specialising in microbiology and antimicrobial resistance (AMR), and currently pursuing a Master’s in Immunology and Clinical Microbiology at Makerere. She is driven by a passion to help reverse the rising tide of AMR, a growing global health threat where drugs that once worked are no longer effective. Kisaakye is particularly concerned about common infections, like urinary tract infections, becoming increasingly resistant and harder to treat.

“I enrolled in this course because I’m an advocate against antimicrobial resistance, and it came at a time when I needed to deepen my knowledge on how to implement our projects more effectively and engage with communities. The experience has broadened my understanding of AMR and its impact on society, and strengthened my passion for community-driven health initiatives and advocacy,” Kisaakye said, explaining why she enrolled for the short course.

Kisaakye’s work in antimicrobial resistance extends beyond the lab. Having earned her degree in medical laboratory science from Mbarara University of Science and Technology, she founded Impala Tech Research in 2024 to drive impact and save lives. She has led grassroots AMR campaigns that integrate antimicrobial stewardship with water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) education in underserved urban communities, including the informal settlements in Kampala. She also has since designed peer-led initiatives that empower university students as AMR Champions, building a network of informed youth advocates. Kisaakye believes the health communication course will sharpen her ability to design and deliver impactful, community-centred interventions in response to the growing threat of drug resistance.

“The department collaborates with many partners within and beyond the University, including the School of Public Health, where we are working to develop the subfield of health communication and promotion. Our goal is to train specialists in this area and build a community of practice, something we have each been doing in our own spaces. There’s a lot of work ahead, and COVID-19 showed us just how urgently we need a generation trained to do this kind of work, and to do it very well,” said Dr. Aisha Nakiwala, Head of the Department of Journalism and Communication, during the opening of the short course on June 5.

She assured participants they were in good hands and underscored the importance of the partnership between the Department of Journalism and Communication and the School of Public Health, describing it as a vital collaboration that brings together strategic communication and public health expertise. This dynamic, multidisciplinary approach, she noted, is essential to developing practical solutions that empower communities, strengthen health systems, and ultimately improve livelihoods.

The course offers a hands-on, multidisciplinary learning experience, with participants intended to explore key modules including Health Communication and Promotion, Risk Communication, Smart Advocacy, Community Mapping, Community Mobilisation and Empowerment, and Strategies for Community Engagement. The course combines theory with real-world application, and its assessment includes a field-based project and a final exam.

“You are our first cohort. We are seeing the fruits of our efforts in bringing this short course to life. It was born out of a joint initiative to develop a Master’s programme in Health Promotion and Communication,” said Dr. Christine Nalwadda, Head of the Department of Community Health and Behavioural Sciences. “We carried out extensive consultations with our different key stakeholders during the process and discovered a real need for such a course. It was the stakeholders who even named it; this course name didn’t come from us.”

For Kisaakye, by the end of the course in July, she hopes to have sharpened her skills in health promotion and strategic communication, particularly in crafting targeted messages that help individuals and communities effectively respond to threats such as antimicrobial resistance. She also aims to gain practical experience in designing, implementing, and evaluating community health initiatives that can strengthen her advocacy and drive lasting impact.

You may like

-

Breaking the Silence on Digital and Gender-Based Violence: Male Changemakers Lead Makerere University’s Strides for Change

-

UNDP and JNLC hold training in Fort Portal: Participants equipped with skills in Advocacy and Gender Equality, Team Building, Inclusive Leadership, and Financial Literacy

-

Makerere University and Tsinghua University Launch Landmark China–Uganda Joint Laboratory on Natural Disaster Monitoring and Early Warning

-

Makerere University Explores Strategic Partnership with Tsinghua University in Safety Science, Disaster Resilience and Public Health

-

College of Humanities and Social Sciences Launches Five Groundbreaking Publications

-

JNLC-JICA Symposium advocates for Inclusive Governance: Amplifies debate on revisiting African-style Governance

Health

MakCHS Strengthens Internationalization through Strategic Global Partnerships and Mobility

Published

4 days agoon

December 30, 2025By

Zaam Ssali

Makerere University College of Health Sciences (MakCHS) continues to advance its internationalization agenda by strengthening cross-border partnerships and expanding student and staff mobility in response to global health training needs. Recognizing international collaboration as a cornerstone of contemporary health professional education, the College has established strategic partnerships with leading institutions, including the University of the Western Cape (South Africa), the Medical University of Graz (Austria), and Universitas Syiah Kuala Faculty of Medicine (Indonesia). These collaborations focus on joint research initiatives and the training of dentists and physicians.

During the period July–September 2025, MakCHS recorded increased inbound student mobility, hosting 86 short-term international students. The majority (73%) came from eight partner institutions, with Europe accounting for 64% of all inbound students. Norway led with students from the University of Bergen and the University of Agder, followed by Italy and the Netherlands. The College also hosted students from Somalia International University, Moi University (Kenya), and institutions in the United States. Most visiting students were medical trainees, with placements mainly in Paediatrics at Mulago National Referral and Teaching Hospital, as well as Emergency Medicine and Obstetrics & Gynaecology at Kawempe National Referral Hospital.

These exchanges demonstrated strong bilateral commitment, notably with the Medical University of Graz, which sent students to MakCHS while simultaneously hosting MakCHS students, even in the absence of Erasmus Mundus Plus funding. Inbound mobility enriched the learning environment through intercultural exchange, inclusiveness, and exposure to diverse clinical and academic perspectives.

Outbound mobility also expanded significantly. MakCHS students undertook clinical rotations in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Austria. Two students completed hematology and oncology rotations at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, while others trained in plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of Minnesota Medical Center–Fairview. Additional students undertook highly specialized rotations in paediatric surgery, orthopaedics, neurosurgery, and cardiac surgery at the Medical University of Graz, gaining exposure to advanced, patient-centred healthcare systems and strengthening their global clinical outlook.

Staff outward mobility was equally notable. Several MakCHS staff and graduate students participated in the Annual Global Health Conference organized by NUVANCE Health, an international partner. MakCHS faculty contributed through presentations, posters, and panel discussions, highlighting research on decolonization in global health education, adolescent health, and global mental health. These engagements provided valuable networking opportunities with global health funders and reinforced the importance of transnational academic partnerships in advancing health equity.

Through sustained partnerships, increased mobility, and active global engagement, MakCHS continues to position itself as a key contributor to global health education, research, and practice.

Health

Makerere University and Tsinghua University Launch Landmark China–Uganda Joint Laboratory on Natural Disaster Monitoring and Early Warning

Published

2 weeks agoon

December 19, 2025

Makerere University has taken a decisive step in strengthening Uganda’s and Africa’s capacity for public safety, disaster preparedness, and climate resilience with the official launch of the China–Uganda Belt and Road Joint Laboratory on Natural Disaster Monitoring and Early Warning, a flagship collaboration with Tsinghua University of China.

Launched during the Makerere University–Tsinghua University Symposium on Public Safety and Natural Disaster Management, the Joint Laboratory positions Makerere as a continental hub for cutting-edge research, innovation, and policy-relevant solutions in disaster risk reduction, early warning systems, and emergency response. The Laboratory will be hosted by Makerere University and is the only facility of its kind in Africa under this cooperation framework, underscoring its regional and global significance.

A Strategic Partnership Rooted in Research, Policy, and Practice

In his opening remarks, Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe, Vice-Chancellor of Makerere University and Ugandan Co-Director of the Joint Laboratory, traced the origins of the partnership to 2018, when a Makerere delegation visited Tsinghua University and the Hefei Institute for Public Safety Research. He recalled being deeply impressed by China’s advanced capacity in public safety research, disaster monitoring, and emergency management capabilities that directly respond to Uganda’s growing exposure to floods, landslides, epidemics, and other hazards.

The Vice-Chancellor noted that the successful establishment of the Joint Laboratory followed a competitive grant process under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, supported by the Government of Uganda and regional partners, including Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire. He emphasized that the Laboratory aligns squarely with Makerere’s strategic ambition to become a research-led and research-intensive university, while also advancing its internationalisation agenda.

“This Laboratory will significantly enhance Makerere University’s ability to generate evidence-based research that directly informs government policy and public safety interventions. It will serve not only Uganda, but Africa at large,” Prof. Nawangwe said.

He further underscored the Laboratory’s national importance, noting that similar facilities in China are regarded as national-level laboratories, entrusted with supporting government decision-making and national resilience. Relevant Ugandan institutions, including the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), UPDF, Uganda Police, Ministry of Health, and humanitarian actors, are expected to actively participate in the Laboratory’s work.

Tsinghua University: Advancing Science Diplomacy and South–South Cooperation

Speaking on behalf of Tsinghua University, Prof. Yuan Hongyong, Dean of the Hefei Institute for Public Safety Research and Chinese Co-Director of the Joint Laboratory, described the initiative as both a scientific milestone and a powerful demonstration of South–South cooperation.

He emphasized that natural disasters transcend national borders and demand collective, science-driven responses. By combining Tsinghua’s technological expertise, including satellite monitoring, AI-driven analytics, and integrated early warning systems, with Makerere’s deep regional knowledge and policy engagement, the Joint Laboratory provides a robust platform for innovation, applied research, and practical solutions tailored to African contexts.

The Laboratory will function not only as a research centre, but also as an operational platform for natural hazard monitoring, early warning, risk assessment, and capacity building, supporting Uganda and the wider African region in building more resilient communities.

Government of Uganda: Research as a Pillar of National Resilience

Representing the Office of the Prime Minister, Mr Frederick Edward Walugemba, reaffirmed the government’s strong support for the Joint Laboratory, recognizing research as a cornerstone of effective public safety and disaster management. The OPM highlighted its constitutional mandate to coordinate disaster preparedness and response through institutions such as the National Emergency Coordination and Operations Centre (NECOC).

He mentioned that the Office of the Prime Minister is committed to working closely with Makerere University and its partners, underscoring the importance of multi-agency collaboration, robust data systems, and timely policy advisories to address the complex, multidimensional nature of public safety challenges.

China–Uganda Relations and the Role of Science Diplomacy

Mr. WANG Jianxun, Commercial Counsellor of the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Uganda, lauded the Joint Laboratory as a concrete outcome of the growing China–Uganda Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. He emphasized that the collaboration reflects China’s commitment to knowledge sharing, technology transfer, and people-centred development, particularly in areas such as climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and sustainable development.

He also highlighted the Belt and Road Initiative as a framework that extends beyond infrastructure to include scientific cooperation, academic exchange, and innovation-driven development, with the Joint Laboratory standing as a model of how universities can advance diplomacy through science.

Makerere’s Multidisciplinary Strength at the Core

In his concluding remarks, Prof. Nawangwe reaffirmed Makerere University’s readiness to operationalize the Laboratory through a multidisciplinary research team spanning public health, geography, engineering, computing, artificial intelligence, social sciences, and the built environment.

He stressed that effective disaster management must integrate technology, human behaviour, governance, and community engagement, noting the importance of sociological insights in addressing risk perception and public compliance during disasters. Makerere will also engage emerging universities and regional partners to ensure the Laboratory’s benefits are widely shared.

The Vice-Chancellor also commissioned an interim, multidisciplinary coordination committee to operationalise the Joint Laboratory, drawing expertise from health, climate science, engineering, artificial intelligence, social sciences, and government agencies.

Hon. John Chrysostom Muyingo Officially Launches the Laboratory

The Joint Laboratory was officially launched by the Honourable John Chrysostom Muyingo, Minister of State for Higher Education, who applauded Makerere University and Tsinghua University for securing the prestigious grant and advancing Uganda’s science and research agenda.

Hon. Muyingo reaffirmed the Government’s commitment to supporting research that informs national development, public safety, and disaster preparedness. He urged Ugandan researchers to fully leverage the partnership to learn from China’s experience in transforming research into actionable solutions for society.

“This Laboratory is a clear demonstration of how strategic international partnerships can strengthen national capacity, inform policy, and protect lives,” the Minister said, as he formally declared the symposium and laboratory launch open.

Positioning Makerere as a Regional Centre of Excellence

Makerere University already plays a critical role in public safety, disaster preparedness, and early warning through a range of research, training, and operational partnerships. Through the School of Public Health (MakSPH) and the Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI), the University has led national and regional initiatives in epidemic preparedness, emergency response, and early warning, including Field Epidemiology Training, risk prediction modelling, and multi-hazard risk assessments that inform district and national preparedness planning. A national assessment of 716 health facilities conducted by MakSPH revealed widespread exposure to climate-related hazards and systemic preparedness gaps, directly informing the Ministry of Health’s Climate and Health National Adaptation Plan (H-NAP 2025–2030)

Makerere has also been at the forefront of disaster risk reduction innovation and community resilience through the Resilient Africa Network (RAN), which has supported scalable, evidence-based solutions such as EpiTent, a rapidly deployable emergency health facility; RootIO, a community-based radio communication platform used for risk communication and early warning; and RIAP Horn of Africa, which advances climate-resilient water harvesting technologies for drought-prone pastoralist communities.

Earlier, the University led the USAID-funded PeriPeri U project (2014–2019) and a disaster management collaboration with Tulane University, strengthening applied research, training, and early warning systems across Africa, efforts that laid the foundation for RAN and Makerere’s current disaster resilience agenda.

In collaboration with government and international partners, Makerere has supported the strengthening of Emergency Operations Centres, including the development of Regional Emergency Operations Centre (REOC) dashboards to improve real-time coordination and situational awareness. IDI has further contributed to epidemic intelligence and early warning, supporting districts to update WHO STAR-based risk calendars, strengthen sub-national preparedness, and enhance real-time decision-making during outbreaks. Makerere teams have also been deployed regionally to support Marburg and Mpox outbreak responses in Rwanda and the DRC, while advancing outbreak modelling as an early warning tool for high-consequence infectious diseases.

Complementing these efforts, the Department of Geography, Geo-Informatics and Climatic Sciences conducts transdisciplinary research on floods, landslides, droughts, soil erosion, and land-use change, using geospatial analysis, earth observation, modelling, and participatory methods to translate complex data into actionable early warning and risk information for policymakers and communities. These ongoing initiatives collectively demonstrate Makerere University’s established capacity in public safety, disaster preparedness, and early warning, providing a strong operational and scientific foundation for the China–Uganda Belt and Road Joint Laboratory.

With strong backing from the Governments of Uganda and China, as well as leading international partners, the China–Uganda Belt and Road Joint Laboratory on Natural Disaster Monitoring and Early Warning is poised to become a regional centre of excellence for disaster risk reduction research, training, and innovation.

The Laboratory will contribute to improved early warning systems, faster emergency response, stronger policy coordination, and enhanced scientific capacity, cementing Makerere University’s role at the forefront of addressing some of the most pressing public safety challenges facing Uganda, Africa, and the global community.

Caroline Kainomugisha is the Communications Officer, Advancement Office Makerere University.

Health

Makerere University Explores Strategic Partnership with Tsinghua University in Safety Science, Disaster Resilience and Public Health

Published

3 weeks agoon

December 16, 2025

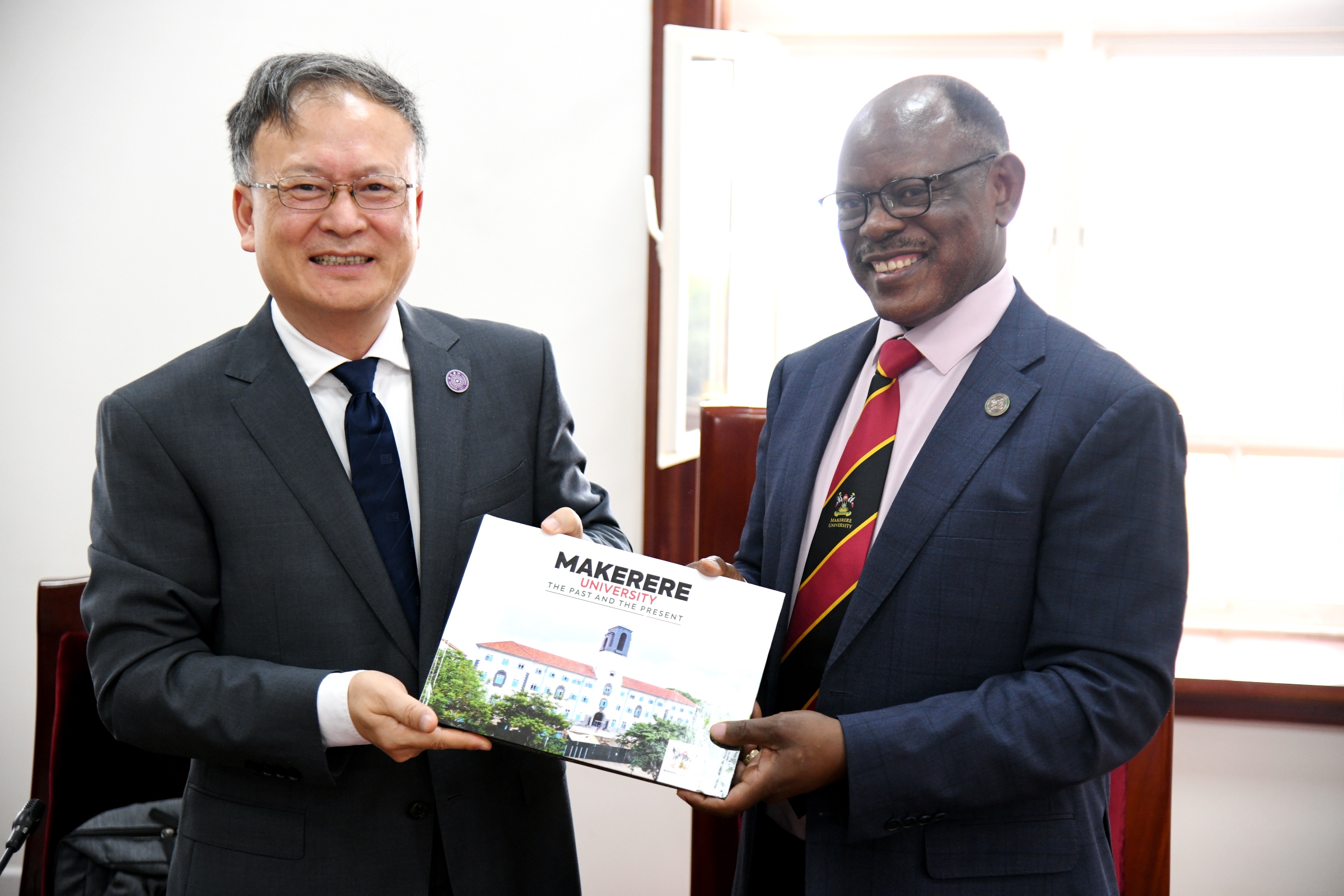

Makerere University has taken a significant step toward strengthening global research collaboration following a high-level meeting between Vice Chancellor Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe and a delegation from Tsinghua University’s Hefei Institute for Public Safety Research, one of China’s leading centres of excellence in disaster prevention, public safety, and emergency management. The engagement marked a renewed commitment to advancing scientific cooperation between the two institutions, particularly in addressing complex environmental and public health challenges that continue to shape national and global development.

A Partnership Anchored in Shared Challenges and Global Priorities

In his remarks, Prof. Nawangwe emphasized that the concept of comprehensive public safety, spanning natural disasters, epidemics, infrastructure failures, and social risks, is increasingly relevant to all colleges and disciplines at Makerere. Uganda’s experience with epidemics such as Ebola, cholera, and COVID-19; frequent landslides in mountainous regions; flooding events; and rising traffic-related incidents place the University in a unique position to contribute applied research, community-based insights, and local knowledge to a global scientific dialogue.

He noted that the Tsinghua presentation revealed new areas of alignment, particularly in epidemic modelling, early-warning systems, and integrated emergency management, areas where Makerere’s public health scientists, medical researchers, and social scientists have extensive expertise.

“This collaboration offers meaningful opportunities for nearly every college at Makerere,” he noted. “Public safety touches the environment, public health, engineering, social sciences, ICT, humanities, and urban planning. The challenges we face as a country make this partnership both timely and essential.” Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe noted.

Tsinghua University: A Global Leader in Comprehensive Public Safety.

The delegation from Tsinghua University outlined China’s national investment in Public safety over the past two decades, an effort driven by the recognition that life and security are the foundation of sustainable development. Tsinghua’s Hefei Institute for Public Safety Research has developed nationally recognised research platforms and large-scale simulation facilities dedicated to Natural disaster modelling (earthquakes, landslides, floods, typhoons, Infrastructure and urban systems safety, Public health emergencies and epidemic preparedness, Early-warning, monitoring, and emergency communication, Traffic and transportation safety, Post-disaster reconstruction and resilience planning.

Their systems currently support over 100 provincial and municipal emergency management centres in China, underscoring their global leadership in practical, scalable solutions for disaster risk management. The delegation reaffirmed that Uganda’s lived experience with multiple hazards presents opportunities for meaningful knowledge exchange. They expressed particular interest in learning from Makerere’s work on epidemic response, community health systems, and the social dimensions of disaster management.

Emerging Areas of Partnership

The meeting identified several promising pathways for long-term collaboration:

1. Joint Research in Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate-Related Hazards

Both institutions expressed readiness to co-develop research projects on landslides, floods, urban resilience, and multi-hazard modelling, drawing on Tsinghua’s advanced simulation technologies and Makerere’s environmental expertise and geographic field realities.

2. Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Epidemic Response

Makerere’s renowned public health schools and research centres will collaborate with Tsinghua on epidemic prediction, early-warning systems, and integrated preparedness frameworks, leveraging Uganda’s decades of experience managing high-risk disease outbreaks.

3. Infrastructure and Urban Safety, Including Traffic Systems

With Uganda experiencing rapid urbanisation and high rates of motorcycle-related road incidents, Tsinghua shared insights from China’s own transformation, including infrastructure redesign, transport modelling, and public transit innovations. Collaborative work in this area would support city planning and road safety interventions in Kampala and other urban centres.

4. Academic Exchange and Capacity Building

Both sides expressed interest in student exchanges, staff mobility, co-supervision of postgraduate research, and specialised training programmes hosted at Tsinghua’s world-class safety research facilities.

5. Development of a Joint Public Safety Laboratory at Makerere

The institutions are exploring the establishment of a collaborative safety research platform in Uganda. This initiative could serve as a regional hub for innovation in emergency management, environmental safety, and technology-driven risk assessment.

Towards a Long-Term, Impactful Collaboration

The meeting concluded with a shared commitment to develop a structured partnership framework in the coming months, supported by both universities and aligned with Uganda–China cooperation priorities. Both teams acknowledged that the partnership must yield tangible results that enhance community resilience, bolster national preparedness systems, and foster scientific capacity for future generations.

Prof. Nawangwe commended Tsinghua University for its willingness to co-invest in research and capacity building, noting that such collaborations position Makerere not only as a leading research institution in Africa but as an active contributor to global scientific progress.

“This partnership has the potential to transform our understanding of the science of public safety to deliver solutions that safeguard lives.” Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe noted.

“It aligns perfectly with Makerere’s mission to be a research-led, innovation-driven university responding to the world’s most urgent challenges.” He added.

As part of this strategic partnership engagement, Makerere University will, on Wednesday, 17th December, co-host the Makerere University–Tsinghua University Symposium on Public Safety and Natural Disaster Management. The symposium will run from 8:00 AM to 2:00 PM in the University Main Hall, Main Building.

This symposium represents a deepening of collaboration not only between Makerere University and Tsinghua University, but also a broader strategic partnership between Uganda and the People’s Republic of China.

During the event, H.E. Zhang Lizhong, Ambassador of the People’s Republic of China to Uganda, together with the State Minister for Higher Education, Government of Uganda, will officially launch the China–Uganda Belt and Road Joint Laboratory on Natural Disaster Monitoring and Early Warning. The Laboratory will be hosted at Makerere University, positioning the University to play a central role in strengthening Uganda’s and the region’s capacity for natural disaster preparedness, public safety, and emergency management research.

Caroline Kainomugisha is the Communications Officer, Advancement Office, Makerere University.

Trending

-

Business & Management2 weeks ago

Business & Management2 weeks agoEfD Uganda Marks 2025 Milestones, Sets Strategic Path for 2025–2029

-

General4 days ago

General4 days agoAdvert for the Position of the Second Deputy Vice Chancellor

-

General4 days ago

General4 days agoUNDP and JNLC hold training in Fort Portal: Participants equipped with skills in Advocacy and Gender Equality, Team Building, Inclusive Leadership, and Financial Literacy

-

General4 days ago

General4 days agoBreaking the Silence on Digital and Gender-Based Violence: Male Changemakers Lead Makerere University’s Strides for Change

-

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoMakCHS Strengthens Internationalization through Strategic Global Partnerships and Mobility