Health

MakCHS Student Innovation shines at HIHA 2021

Published

4 years agoon

By

Zaam Ssali

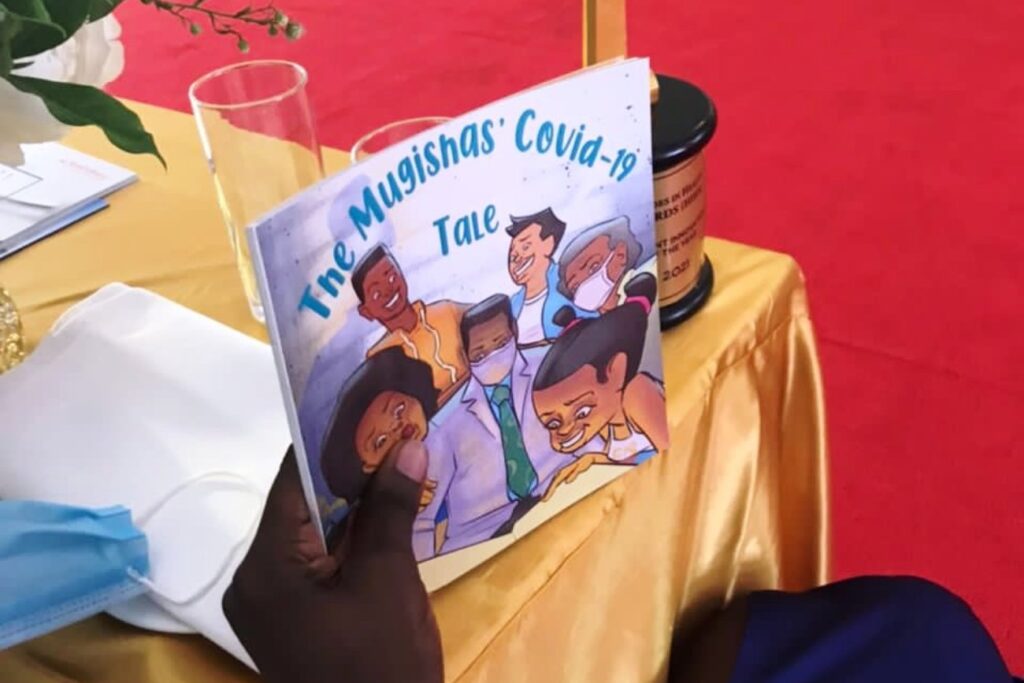

A team of students led by Ms. Anna Maria Gwokyalya – 4th year student of Medicine and Surgery at the College of Health Sciences (MakCHS), Makerere University won the award of ‘Student Innovation of the Year’ at the Heroes in Health Awards (HIHA) held on the 12th November, 2021. Her innovation was a book “The Mugishas’ COVID-19 Tale” designed to help children be more involved in the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic.

Inaugurated in 2019, The Heroes in Health Awards (HIHA) is a public private initiative adopted by the Ministry of Health with the support of Xtraordinary Media to offer opportunity to members of the public to motivate Uganda’s excellent health sector players, recognize and encourage new innovations that will transform our health care system.

Anna Maria shares the experience of the team in an interview below:

Tell us more about your team

We are a team of five students who have worked on numerous research projects and online campaigns to increase awareness of Antimicrobial Resistance under ARSU (Antimicrobial Resistance Stewardship Uganda). Whereas I was the leader of this comic book project, it’s the brainchild of the entire team, an indicator of respect, mutuality and friendship.

Describe your innovation and what motivated you to work on it

This book entitled, “The Mugishas’ COVID-19 Tale” contains fascinating illustrations with simplified information on symptoms, transmission and prevention of COVID-19 that includes both observation of the standard operating procedures and vaccination.

The book is a means of creating awareness on COVID-19 disease and its prevention among children below 12 years, a vulnerable group that is not eligible for vaccination (as per Uganda’s Vaccination Guidelines) against this disease, we designed the book to help children be more involved in the fight against this disease.

Infection prevention and control is not only pertinent to fighting Antimicrobial Resistance but also to promotion of health and wellbeing of the people. Writing this book is our contribution to controlling of infection as well as prevention, an important aspect of primary health care.

What is the impact of the book from your perspective?

Since the comic book is very illustrative and appealing to the eye, we anticipate that the children will gain knowledge on COVID-19 as they enjoy the illustrations. We also hope that they will be agents of change through sharing this knowledge with their peers both at home and at school, protecting them against the disease in the long run.

What is your advice to others about new ideas and innovations?

My advice is drawn from two quotes;

Quote 1: “Find something you’re passionate about and keep tremendously interested in it.” – Anonymous

Quote 2: “Teamwork is the secret that makes common people achieve uncommon results” –Ifeanyi Enoch Onucha

Innovations by MakCHS Research teams were exhibited at the HIHA Awards as well. These included:

VITEX (Medical Assistance Tool): Vitex is an integrated system that utilizes antimicrobial and affordable 3D plastics made out of 80% waste plastic, making it eco-friendly. The device sterilises wards up to 99.9%, thus preventing nosocomial infections by employing powerful pulsating U.V engine and spots latest in artificial intelligence to improve patient care and practitioner assistance.

Vitex is intended to improve health professionals’ quality of work by reducing workload and deters transmission of highly contagious infections such as COVID-19. It also improves access to vital medical literature, facilitates electronic consultation, service delivery in the medical environment, including carrying out consistent patient monitoring and reducing prescription/medication errors.

The device spots a Powerful Artificial Intelligence package that incorporates Intel RealSense, auto-follow, video capture, touch & voice control, playful expressions, and personality to keep patients in a cheerful mood. Vitex includes over-the-air updates making it viable for endless integration, including providing seamless data access for important time-sensitive decision-making through elaborate integrations.

Team: Dr. Justine Nnakate Bukenya (PI), Ainembabazi Samantha, Joeltta Nabungye, Kiirya Arnold, Mugisha Gift Arnold

The Early Preeclampsia Detection Strip (EPED Strip): The Early Preeclampsia Detection (EPED) Strip is a urine-based point-of-care detection strip for preeclampsia that pregnant women can use at home to self-screen for the condition. Preeclampsia is a maternal condition characterized by high blood pressure of 140/90mmHg and proteinuria after 20 weeks of pregnancy. Worldwide the condition is responsible for over 500,000 infant deaths and 70,000 maternal deaths annually. By seeking medical care at the early onset of preeclampsia, the condition can be appropriately monitored and controlled, thereby reducing the detrimental health impacts of undiagnosed preeclampsia which is a health burden to LMICs. Thus, the EPED strip is being designed to diagnose this condition early and functions very similar to a pregnancy test where urine is applied to one end of the strip, and pulled across it by capillary attraction to where antibodies specific to the biomarkers are immobilized. In the reaction matrix there are two lines, a test line and a control line. The presence or absence of the control and test lines indicates the presence or absence of the captured conjugates. This is designed with adaptation from the existing lateral flow assay (LFA) technology. While the primary goal of the EPED strip is to be a home-based early detection tool, the EPED strip can also be used to assist the diagnosis of preeclampsia in a clinical setting from large-scale national hospitals to remote health clinics.

Team:Prof Paul Kiondo (PI), Brian Matovu, Zoe Ssekyonda, Calvin Abonga, Olivia Peace Nabuuma, Dr. Robert Ssekitoleko

The Maternal PPH Wrap: The maternal PPH wrap; a wearable device strapped around the mother’s waist; affordable compared to the other devices that is able to carry out external compression of the uterus through the abdominal wall in order to stimulate myometrium contraction. The design is based on already used bimanual uterine compression techniques which are manually done by qualified and skilled personnel.

Despite the number of interventions, postpartum haemorrhage still remains the leading cause of maternal death globally. Most of the interventions that are recommended under standard clinical practical guidelines such as uterotonic drugs, therapeutic devices or even surgery are unavailable in the communities of low and middle income countries including Uganda simply because they are unaffordable and most times require qualified/skilled personnel and highly sterile environments.

The device will rely on an inflatable rubber bag to provide the pressure to do the sustained compression. The inflation will be done using a bulb similar to the one used by a sphygmomanometer. This is way less labour intensive than the procedure of bimanual uterine compression. The overall aim Is to create an efficient device that is affordable in Uganda and all developing countries’ healthcare markets as a leading lifesaver of mothers.

Team: Owen Muhimbisa, Kiwanuka Martin, Arinda Beryl, Maureen Etuket, Denis Mukiibi, Robert Ssekitoleko.

Zaam Ssali is the Principal Communication Officer SoL & MakCHS

You may like

-

Makerere Graduation Underscores Investment in Africa’s Public Health Capacity

-

Makerere’s 76th Graduation Ceremony: CHS showcases research strength with 26 PhD Graduates

-

Medical graduates urged to uphold Ethical values

-

Philliph Acaye and the Making of Uganda’s Environmental Health Workforce

-

76th Graduation Highlights

-

Olivia Nakisita and the Quiet Urgency of Adolescent Refugee Health

Health

82% Stressed: Uncovering the Hidden Mental Health Burden Among Kampala’s Taxi Drivers

Published

1 day agoon

March 12, 2026

A new study by Dr. Linda Kyomuhendo Jovia, a medical doctor and graduate of the Master of Public Health programme at Makerere University School of Public Health, has found high levels of psychological distress among minibus taxi drivers operating in Kampala’s major taxi parks. In a cross-sectional survey of 422 drivers across Old, New, Kisenyi, Usafi, Namirembe, Nakawa, and Nateete parks, nearly two-thirds screened positive for symptoms of depression (65.6%), while anxiety affected more than 70%, and stress an estimated 82%. The findings point to a largely overlooked occupational health concern within the city’s informal transport sector, where long working hours, economic pressure, poor sleep, and prior road accidents were associated with higher levels of mental strain.

Before sunrise settles over Kampala, Old Taxi Park is already awake. White minibuses marked with the blue stripe of Uganda’s public service taxis sit jammed bumper to bumper, their noses pointed toward narrow exits that will soon release them into the city’s traffic. Dust clings to the windows. Torn seats peek through sliding doors. Diesel hangs low in the air. Conductors slap the metal sides of vans and shout destinations into the morning.

“Kireka! Banda! Bweyogerere!” The calls overlap until they become a steady roar.

Passengers squeeze through narrow corridors between vehicles where there was never meant to be walking space. Hawkers weave through the crowd with trays of roasted maize and boiled eggs. Somewhere, a small radio crackles. Nearby, two conductors argue over whose turn it is to load passengers. This scene is how Kampala wakes, in diesel fumes, shouted destinations, and the quiet urgency of people trying to earn a living before the traffic tightens its grip on the day.

Handwritten route boards fixed to the taxis signal their destinations: Masaka “A” Stage, Kaguta Road, Nakawa, Namirembe, Ntinda, Gayaza, Nansana, and Entebbe, guiding passengers through the organised chaos of the park. Behind every steering wheel sits someone doing the arithmetic of survival. Drivers wake before dawn to secure a place in the queue. For many, sleep is short, interrupted, and rarely restorative. The day stretches across long hours of traffic, uncertain earnings, rent, school fees, and taxi levies, including annual payments of about UGX 720,000. Passengers today mean dinner tonight. Yet inside the noise of the taxi parks, another story has remained largely invisible.

Across Uganda, an estimated 400,000 taxis move millions of passengers every day, forming the backbone of the country’s informal transport system. But almost nothing is known about the psychological toll on the drivers who keep it running.

That gap is what drew Dr. Kyomuhendo into Kampala’s taxi parks. What she uncovered were levels of depression, anxiety, and stress far higher than many had imagined.

A Medical Doctor Turning Toward Public Health

Born on 23 July 1994 to Mr. Muhigwa Lawrence and Ms. Kataito Jacqueline, Dr. Kyomuhendo grew up in Hoima District in western Uganda. Her early education took her from St. Christina Nursery School to Budo Junior School before she continued to Trinity College Nabbingo and later Mount Saint Mary’s College Namagunga for Advanced Level, where she studied Biology, Chemistry, and Mathematics.

In 2014, she earned a government scholarship through the Public Universities Joint Admissions Board and enrolled for a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery at Busitema University, graduating in 2019.

During her medical internship at Masaka Regional Referral Hospital, she began noticing a troubling pattern in the cases arriving at the wards: road traffic injuries, complications of chronic diseases, severe malaria in children, and obstetric emergencies that might have been prevented with earlier intervention. Many of the crises doctors were treating, she realized, had begun long before patients reached the hospital. “They were symptoms of deeper problems,” she recalls.

Public health offered a way to investigate those underlying causes. In 2022, she enrolled in the Master of Public Health Distance programme at Makerere University School of Public Health, where students are trained to examine health problems not only at the bedside but across entire populations. Guided by Associate Professor Lynn Atuyambe, a respected scholar in Community Health and Behavioural Sciences at MakSPH, and Dr Juliet Kiguli, Senior Lecturer and public health anthropologist, the student’s work benefited from strong academic stewardship.

Uganda’s road transport system is dominated by motorcycles and 14-seater minibus taxis. About 15,000 operate in the Kampala Metropolitan Area alone.

These drivers navigate congested roads, pollution, erratic traffic patterns, and long working hours. Their workday often begins before dawn and stretches deep into the evening.

“They are important in Uganda’s transport industry,” Kyomuhendo said. “Yet they seem to be overlooked in our society.”

While commuting through Kampala during her studies, she began to notice the lives of taxi drivers. Arguments between passengers and conductors were common. When tensions rose, someone would eventually mutter the same question in Luganda.

“Oba abasajja ba takisi baabaki?” loosely to mean, ‘What is wrong with taxi men?’

The question lingered, and in June 2024, social media campaigns marking Men’s Mental Health Awareness Month pushed her to think about the issue differently. What if the behaviour many passengers dismissed as impatience or aggression was linked to something deeper? To her, taxi drivers seemed an unlikely but revealing group to study.

“They carry the responsibility for passengers’ lives every day,” she says. “Yet very little attention is paid to their own well-being.”

For instance, Kampala City Authority (KCCA) documents that between 2019 and 2024, geolocated crash data reveal a dangerous road environment in which Kampala’s taxi drivers operate daily. A total of 1,878 vulnerable road users, including pedestrians, motorcyclists, and cyclists, were killed in crashes involving motor vehicles, with buses and minibuses linked to 281 deaths, most of them pedestrians (147) and motorcycle occupants (131). Fatalities were heavily concentrated along major corridors such as Jinja Road, Kibuye–Natete Road, Bombo Road, and Ggaba Road, while for pedestrians, the most dangerous segments included Gayaza Roundabout (Kalerwe) and Kyebando Police Post along the Northern Bypass and Entebbe Road, where fatality densities reached 27–28 deaths per kilometer. These patterns highlight the high-risk traffic environments in which taxi drivers work, specifically busy arterial roads and bypass intersections where pedestrians, boda bodas, and public transport vehicles compete for space. These conditions contribute to the broader pressures that shape drivers’ safety, well-being, and mental health.

Research in the taxi parks

Her dissertation set out to answer two questions: how common are depression, anxiety, and stress among taxi drivers in Kampala, and what factors contribute to them? The study surveyed 422 male drivers across seven major taxi parks: Old, New, Kisenyi, Usafi, Namirembe, Nakawa, and Nateete, using a multistage sampling approach designed to ensure representation across the city’s transport hubs.

Participants completed structured interviews on socio-demographic, occupational, lifestyle, use of habit-forming substances, medical, and environmental factors. Mental well-being was assessed using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21), a widely used screening tool in mental health research.

The data were analysed using statistical models that allowed Kyomuhendo to examine how occupational conditions, lifestyle factors, and health status interacted to shape mental well-being.

The study reflected the epidemiological training embedded in MakSPH’s Master of Public Health programmes, where students are encouraged to investigate real-world health challenges through evidence-based research.

Conducting interviews inside the taxi parks meant stepping into one of the most unpredictable environments in the city. “The atmosphere was survival for the fittest,” Kyomuhendo recalls.

Stories behind the statistics

The fieldwork brought moments that stayed with her long after the questionnaires were completed. One driver laughed when asked how he coped with stress. “I don’t drink or smoke,” he said, suggesting that multiple relationships were his way of managing the emotional strain of the job.

The answer was not in the questionnaire, and they both laughed. Yet the moment captured something deeper about life in the taxi parks: humour often hides exhaustion.

Another driver told her he had spent years buying herbal medicine for a hernia that never healed. Every month, he spent close to 100,000 shillings, hoping the treatment would eventually work. She advised him to seek hospital care, a conversation that stayed with her.

“Sometimes people spend far more trying to manage a problem than it would cost to treat it properly,” she explains.

When the data were analysed, nearly two-thirds of the drivers screened positive for symptoms of depression. More than 70 percent had symptoms of anxiety, and over 80 percent reported levels of stress. The psychological burden was far heavier than most people had assumed.

Several factors stood out. Drivers who had experienced road accidents in the previous year were significantly more likely to report depression. Chronic medical conditions and a family history of mental illness also increased the risk.

Sleep deprivation emerged as one of the most important predictors. Drivers who consistently slept fewer than seven hours per night were far more likely to report anxiety and stress. Also, economic security mattered. Drivers who owned their vehicles were substantially less likely to experience anxiety compared to those who rented taxis or paid daily remittance fees to vehicle owners. In other words, psychological distress followed the same lines as economic pressure.

More than a transport problem, and the silence around men’s mental health

The implications extend beyond the drivers themselves, she observed. Mental health affects concentration, reaction time, and decision-making. All abilities that are critical for safe driving in a city known for congestion, unpredictable traffic, and frequent road hazards, including flooding, among others.

“If drivers are anxious or sleep-deprived,” Kyomuhendo explains, “there is a risk they may struggle to follow traffic rules or respond quickly to hazards.”

In a transport system that carries millions of passengers daily, the well-being of drivers becomes a matter of public safety. The findings suggest that mental health among taxi drivers should be treated as both an occupational health issue and a transport policy concern.

During interviews, Kyomuhendo noticed another pattern. Few drivers openly described themselves as depressed or anxious. Instead, stress appeared through jokes, casual references to alcohol or relationships, or long pauses followed by silence.

Men’s mental health remains a difficult subject in many communities. “Men’s mental health is a serious public health issue that should not be ignored,” she says.

Breaking the stigma will require awareness campaigns, stronger occupational protections, and greater attention from both health authorities and transport regulators, she proposes.

A different way of seeing the city?

This research also changed how Kyomuhendo sees Kampala. Where passengers notice congestion or impatience, she now sees the pressures shaping the people behind the wheel. “It made me appreciate the men who show up every day and work hard despite their struggles,” she says.

One driver confided in her about the pressures of the job. “People will not help you unless they know the problems you are facing,” he said.

The city and its drivers

By late afternoon, the taxi parks are as crowded as they were in the morning. Conductors still shout destinations into the traffic. Engines idle in long rows of white vans waiting for passengers. Drivers lean against steering wheels, hoping the next arrival will finally fill the vehicle.

The city keeps moving because they do. Most passengers step into these taxis thinking only about where they are going—work, home, school, or the market. Few stop to consider the pressures carried by the people behind the wheel.

Yet Kyomuhendo’s research suggests that beneath the noise of the taxi parks and those car hoots on the streets lies something far quieter and far less visible: a level of stress, anxiety, and depression that touches not only the drivers themselves but also the safety of the passengers they carry and the communities they serve.

Each morning, the vans will still line up bumper-to-bumper. Conductors will still shout destinations into the traffic. Kampala will still climb inside and move.

If nearly half a million taxis keep Uganda moving every day, who is protecting the minds of the people behind the wheel?

Health

Makerere Graduation Underscores Investment in Africa’s Public Health Capacity

Published

1 week agoon

March 4, 2026

KAMPALA, 25 February 2026 — Higher education must move beyond awarding degrees to producing solutions for national and global crises, speakers said on Wednesday as Makerere University continued its 76th Graduation Ceremony, positioning universities as central actors in strengthening Africa’s public health capacity.

Addressing graduands on Wednesday, February 25, 2026, at Freedom Square, national leaders and university officials framed graduation not as a ceremonial endpoint but as an investment in workforce readiness, research leadership, and evidence-driven governance, particularly at a time when health systems across the continent face growing pressure from pandemics, demographic change, and climate-related risks.

The message resonated strongly through presentations from Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH) and Makerere University College of Health Sciences (MakCHS), whose graduates enter professional service amid renewed global attention to health system resilience, scientific leadership, and locally generated research.

Delivering the commencement address on Day Two of Makerere University’s 76th Graduation Ceremony, Dr. Margaret Blick Kigozi, Board Chairperson of the Makerere University Endowment Fund, reflected on her graduation in 1976 during a period of national uncertainty under then-Chancellor President Idi Amin. She recalled leaving Uganda soon after with her young family, carrying “little more than education, values, and hope,” an experience she used to frame lessons on resilience, purpose, and responsibility in uncertain times.

Challenging graduates to rethink professional success, she reminded those entering health and life sciences that their training carries extraordinary influence.

“Power does not make you important; it makes you responsible,” she said. “You will decide who is listened to and who is dismissed, who waits and who is rushed through, who feels safe and who feels small. Your education has trained you to ask better questions, but your humanity must guide the answers. Behind every chart, every case, every experiment, there is life, and life deserves care, patience, and dignity.”

Throughout the ceremony, speakers returned to a common refrain: societies increasingly depend on evidence, and universities must produce professionals capable of translating knowledge into policy, practice, and community impact.

Across the four-day congregation, the University will award 9,295 degrees and diplomas, including 2,503 Master’s degrees, 6,343 Bachelor’s degrees, 206 Postgraduate Diplomas, and 30 Diplomas. But beyond the numbers, speakers repeatedly returned to a central question on how higher education can translate academic growth into national development and health security.

On day two, graduands were presented from the College of Natural Sciences, the College of Veterinary Medicine, Animal Resources and Biosecurity, the College of Health Sciences, and the MakSPH, the latter positioned squarely within Africa’s ongoing struggle to expand its pool of trained epidemiologists, health systems researchers, and policy leaders.

Vice Chancellor Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe noted that Africa averages just 80 researchers per million people, compared to a global average of 1,081, warning that the human resource gap remains substantial.

“Today the School of Public Health presents graduands joining the field at a time when Africa faces a critical shortage of highly trained public health leaders,” he said.

The School of Public Health presented seven PhD candidates: Aber Harriet Odonga, Komakech Henry, Lubogo David, Nakisita Olivia, Namukose Samalie, Ntaro Moses, and Osuret Jimmy. It also graduated 195 Master’s students and 29 Bachelor of Environmental Health Science graduates, including four first-class honours recipients led by Phillip Acaye with a CGPA of 4.63.

Their research spans maternal and child health, epidemic preparedness, sanitation behaviour change, nutrition systems integration, and injury prevention, areas increasingly recognised as foundational to national development rather than peripheral health concerns.

University Chancellor Dr. Crispus Kiyonga emphasized that research must move beyond academic publication into policy and implementation.

“Research plays a very vital role in the development of any community,” he said, linking university scholarship directly to Uganda’s national development agenda.

For public health education, that responsibility carries particular urgency. The COVID-19 pandemic, recurring disease outbreaks, and climate-linked health risks have exposed how deeply national stability depends on scientific capacity.

The chancellor hailed the Government of Uganda for committing UGX 30 billion through the Makerere University Research and Innovations Fund (MakRIF).

Mak Urged on More PhDs

Representing the First Lady and Minister of Education and Sports, State Minister Dr. Joyce Kaducu Moriku described doctoral training as central to Uganda’s research ambitions, noting government efforts to expand funding and modernize higher education systems.

“Universities must produce more PhDs to strengthen the national research agenda,” she said, adding that competence-based reforms aim to align training more closely with societal needs.

“More PhDs also mean the university is growing in academic leadership and an increase in research. So, keep the numbers growing, especially in Science, Technology, and Engineering,” she added.

The 213 PhDs conferred this year, a record, signal more than institutional expansion but a response to structural deficits.

Africa bears approximately 25% of the global disease burden but produces a disproportionately small share of global health research. The continent’s research density remains far below global averages. In this context, each doctoral graduate becomes not merely an academic achievement but a strategic asset.

A University Responding to Its Moment

For the School of Public Health, the graduation reflects a broader evolution in how public health training is conceived. Rather than focusing solely on the treatment of disease, the field increasingly addresses systems, sanitation, nutrition, behavioural change, surveillance, prevention, and climate change, areas where research directly shapes everyday life.

Recent MakSPH-led initiatives, including national HIV impact surveys and digital health system expansion, demonstrate how academic institutions increasingly function as implementation partners to the government rather than observers.

Over the past five years, MakSPH has supported the national scale-up of electronic medical records through the CDC-funded Monitoring and Evaluation Technical Support (MakSPH-METs) programme, and led the Third Uganda Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment (UPHIA 2024–2025), the first fully Ugandan-implemented national survey of its kind.

Launched in 2020, the METs program has supported the nationwide scale-up of UgandaEMR+, transitioning thousands of facilities to secure electronic medical records and deploying critical ICT infrastructure. In March 2026, these systems will be formally transitioned to the Ministry of Health, reflecting sustainable national ownership.

Health

Three MakSPH Faculty Honoured with Makerere University Research Excellence Awards 2026

Published

2 weeks agoon

March 2, 2026

KAMPALA—Three faculty members from Makerere University School of Public Health (MakSPH) have been recognised at the Makerere University Vice-Chancellor’s Research Excellence Awards 2026, highlighting the School’s expanding contribution to research leadership, scientific productivity, and policy-relevant scholarship across Africa.

Associate Professor Peter Kyobe Waiswa, Associate Professor David Musoke, and Juliana Namutundu received honours during the University’s 76th Graduation Ceremony at Freedom Square, where Makerere celebrated scholars whose work has demonstrated exceptional research achievement and impact beyond academia.

The annual awards, coordinated by the Directorate of Research, Innovation and Partnerships (DRIP), recognise faculty and staff whose scholarly output and leadership advance Makerere University’s ambition to become a research-led institution.

“This recognition celebrates sustained excellence in research productivity and contributions to knowledge that advance both national and global discourse,” Vice-Chancellor Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe said. “We are strengthening a culture where research does not remain confined to journals but translates into solutions for society.”

Among the university’s top researchers was Assoc. Prof. Peter Kyobe Waiswa, a health systems scientist whose work focuses on maternal, newborn, and child health. Waiswa ranked among Makerere’s overall top researchers after publishing 43 peer-reviewed papers in 2025, tying with three-time award winner Prof. Moses Kamya of the School of Medicine in the College of Health Sciences.

His research examines how health systems function at their most fragile moments, including childbirth, early life, and community-level care, addressing questions of equity, service delivery, and health system performance across Africa.

Also recognised was Dr. David Musoke, an Associate Professor of Disease Control, whose 25 publications earned distinction among senior career researchers. His work spans environmental health, community health systems, and implementation research, areas increasingly viewed as critical to preventing disease before it reaches hospitals.

In the early-career category, Juliana Namutundu received recognition for emerging research leadership, reflecting Makerere’s effort to nurture the next generation of African scholars.

Together, the awards underscored MakSPH’s growing influence within Makerere’s research ecosystem, particularly in fields linking science directly to population wellbeing.

The Research Excellence Awards were established to encourage publication in high-impact journals while reinforcing Makerere’s ambition to become a globally competitive research university. Nominations are reviewed by the Board of Research and Graduate Training, chaired by Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic Affairs) Prof. Sarah Ssali.

Awardees were honoured during a graduation luncheon organised by the Makerere University Convocation, the institution’s alumni and staff association, which described the event as a celebration of “excellence and inspiring impact.”

The ceremony also recognised forms of scholarship extending beyond traditional academic publishing.

Dr. Geofrey Musinguzi, a research associate at the School of Public Health, was honoured for his book My Journey with Rectal Cancer, an account of diagnosis, treatment, and recovery that blends personal testimony with public health advocacy.

Diagnosed at age 44 while a visiting scholar at the University of Antwerp in Belgium, Musinguzi sought medical care after experiencing persistent symptoms, including rectal bleeding and back pain. His treatment involved surgeries, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and a year living with a colostomy bag.

Rather than keeping the experience private, he documented it publicly to challenge cancer stigma and encourage early screening. The book, launched at the School of Public Health in August 2024, highlights how lived experience can shape public health awareness alongside scientific research.

The recognition reflects a broader understanding of research impact, one that includes scholarship capable of influencing behaviour as well as policy.

Makerere’s emphasis on research excellence comes as African universities face increasing pressure to produce locally grounded evidence while competing globally for visibility and funding. For MakSPH, whose work spans disease surveillance, environmental health, and health systems research, publication output increasingly serves as both academic currency and development infrastructure.

“These awards are part of our broader effort to position Makerere as a truly research-led institution,” Nawangwe said, adding that scholarship must remain aligned with national and regional priorities.

Trending

-

General1 week ago

General1 week agoCall for Applications: Diploma Holders under Government Sponsorship 2026/2027

-

General1 week ago

General1 week agoAdvert: Admissions for Diploma/Degree Holders under Private Sponsorship 2026/27

-

General1 week ago

General1 week agoExtension of Application Deadline for Diploma/Degree Holders 2026/2027

-

General2 weeks ago

General2 weeks agoMakerere University commemorates 13 transformative years of partnership with Mastercard Foundation

-

General1 week ago

General1 week agoMakerere University and World Bank Sign Partnership to Strengthen Environmental and Social Sustainability Capacity